2187 words/15 minutes

I first met Jacques Ngoun, a Bagyeli Pygmy from south Cameroon, at a IUCN run forest conservation conference, on the first few days of my first visit to Cameroon in February 1999. The conference, took place at the Yaounde Hilton, a vast, vastly expensive, and entirely inappropriate location for a discussion on forest policy, poverty alleviation and social justice.

I stood talking to Simon Counsel of the Rainforest Foundation-UK and Margaret of Forest People’s Programme (FPP) outside the conference room, waiting for the Cameroon Minister of Forests to open the conference, which was scheduled for 9am. After two hours, a bevy of military, holding semi-automatics, ushered the minister into the conference room. The minister gave a short, empty and trite speech, with armed soldiers standing menacingly behind him and others guarding the door. Having held a hundred or more people up for two hours, he swept out with his armed guard. The other speakers were no better: a foreign expert on how villagers must be educated to protect the forest, a technical expert on some arcane aspect of forestry law, a World Bank official on conditionalities and development loans.

Tragically, tropical rainforest logging, legal as well as illegal, is the root cause of rainforest destruction in Africa. Villagers are not consulted about whether logging takes place, and do not benefit from it, (though the local chief may soon be driving a brand new 4×4 courtesy of the logging company). Their forest is mutilated, and the game hunted out to feed the loggers, who have cash. The logging operation quickly moves on, leaving the consequences, but few if any economic benefits. This is far worse for Pygmy peoples, who do not farm in second growth forest, but live, hunt and gather in old growth. A conference that ignores this, describes technical issues, and blames the villagers for the problem is clearly worse than useless. Most logging is simply monetising a local resource that provides benefits (food, medicines and other non-timber forest products) to the local population in perpetuity into a quick gain for a international logging company and corrupt officials, local and national.

The fact that logging was corruptly controlled by government ministers and senior generals, who used it for personal enrichment and ignored all legal and ecological regulation, and that the presidents nephew was the biggest concession holder in the country, was not mentioned. We were told the problem was caused by ignorant villagers. Jacques, who talked about the relationship of Pygmy peoples to the forest, “without the forest, we will die as a people,” was the only person who spoke at the conference who was not compromised by being paid off or employed in the corrupt processes involved in logging Cameroon’s rainforests.

I was introduced to Jacques by Margaret of the FPP. We got on instantly, and he invited me to visit him near Bipindi 230 kilometres south of Yaounde. Margaret then asked me if, while I was there, I’d evaluate a FPP proposal to purchase a satellite phone for Jacques. I was happy to help a local activist get access to resources, and later I got a briefing on the proposal and its budget of £6,000.

Next day, after Jacques returned home to Bipindi, I met with Didier Amagou of local NGO Planet Survey, who had an office in Lolodorf, en route for Bipindi. A few days later, I made my way through the very early morning darkness to meet Planet Survey, but through one delay or another we left Yaounde at almost 6 am and the roads were already crowded with people walking into Yaounde in the dark. Terrible driving is one of the perennial dangers of working in Africa, but I was far more concerned for the men, women and children walking along the edge of the narrow roadway in the dark to get to their fields, jobs or schools, as we hurtled past lurching across the road to avoid the potholes.

This was the first time I’d been out of Yaounde, the first time I’d been on a “field visit” in Africa, and I was excited at getting out of the hotel conference, international expert bubble. We drove for an hour along the Douala road, and turned off at a busy crossroads filled with small food stalls. Street traders and fruit sellers crowded around overcrowded buses stopping for a break on their journey. In another hour or so, we were at Lolodorf, a small German colonial town astride the Lokoundje River. I was given a tour of the Planet Survey office, and got to meet about a dozen local staff.

After lunch we set off again, on a field visit to a Pygmy encampment. This was a first contact visit, with Planet Survey introducing themselves and identifying what services the camp might need. It seemed a rushed affair, with Planet Survey doing a brief introduction on their work and leaving little time for discussion before hurriedly returning to Lolodorf. That evening I went out dancing with many of the Planet Survey staff in a bar with a stereo, some red spotlights, and plenty of choices in beer. It was a great night out. We created a real party atmosphere with just fifteen people; and the director of Planet Survey had some mean dance moves.

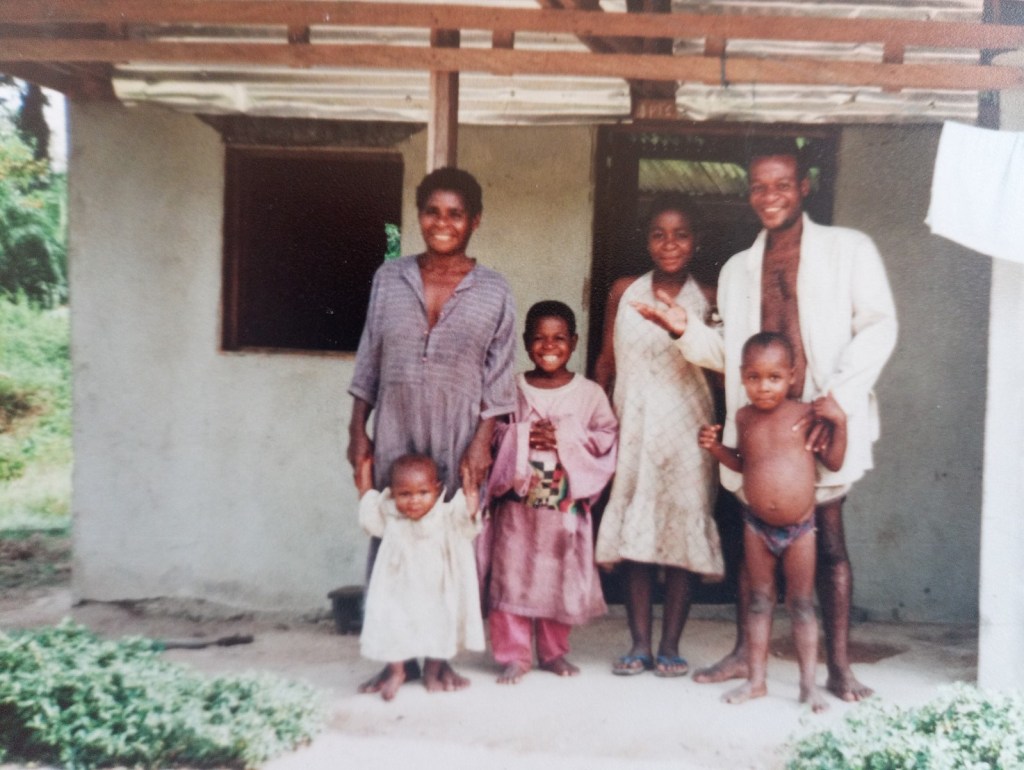

The next day Planet Survey offered to combine taking me to Jacque’s house with a field trip to the Bipindi area, so I contributed a tank of gas for the jarring 45 km drive down the rocky road which followed the steep Lokoundje river gorge to the small town of Bipindi. There we visited the Foire, a Catholic school for apprentices, where Jacques had once worked. An hour later I was dropped off at Jacques house, four miles outside Bipindi. I got a great, enthusiastic greeting, and met Jacques wife and numerous children.

I stayed for three nights with Jacques at his house, eating wonderful meals of game meat, manioc and delicious sauces made with fresh ground herbs and spices. We made trips into the surrounding fields to drink palm wine straight from the palm tree. The owner of the wine palm was a local farmer called Simon too, who was introduced to me as my homonym Simon.

Jacques told me about his history- he is a Bagyeli but was brought up by a Bantu family. He wanted to show that the Bagyeli were responsible people who could live in a ‘proper’ house and live like a Bantu. This acculturation seemed sad to me, but I was new and held my counsel. Each day we swam and bathed in the river, met Jacques neighbours, talked about life in the village and about CODEBABIK, the Bagyeli organisation which Jacques represented as director of programmes.

Jacque’s son was about twenty. He’d recently qualified as a carpenter, in a college in Kribi on the coast, but was unable to work as he hadn’t the money to buy the tools he needed to set up a workshop. (I had questions about his future as the Bagyeli used the most basic furniture, and lived from hand to mouth, and about who among the people in Bipindi could afford to buy hand-made furniture.)

Jacques himself was neatly turned out, but his children were dressed in filthy, torn rags. There was a small piece of soap in the house, used to wash hands occasionally. But there was not the money to buy soap for all to wash themselves and their clothes. I struggled to understand the economics and cultural background that made all this happen.

On the fourth day, I joined Jacques and his wife and the baby on a walk along the dirt road out of the village, and through the second growth forest for several hours. We turned off along a track into the forest to a Bagyeli village, where a dozen Bagyeli greeted us. Two of Jacques children were already there. Jacques held a meeting with the men and his wife with the women while I wandered around the huts and into the surrounding forest and took pictures. That night there was music and song by the fireside. I slept in a palm hut under my mosquito net.

Most of the villagers were further into the forest at a hunting camp. I hoped to join them, but it was not possible as Jacques had to return to Bipindi for a meeting with CODEBABIK. Next day we returned to Bipindi and my first field-trip finished with a walk through the fields and forest to a dugout ferry across the Lokoundje to Bipindi and the bus to Kribi on the coast.

Before I left to return to the UK, I heard that the Rainforest Action Network-RAN was attending a planning meeting near Munich, and had invited Didier Amagou of Planet Survey. I persuaded their Africa project coordinator, for whom I had done research in Cameroon, that both Jacques and I should attend too. The evening I got to the meeting, near a lake south of Munich, I discovered that the itching in my big toe that had been troubling me, was caused by a maggot growing in my foot. I asked my Cameroonian colleagues what to do, and was told to get hold of a single-bladed razor. I asked the volunteer going into Munich the next day to get me one. It was very difficult getting through the night, and all of the next day, now that I knew that the itch was caused by a live maggot in my toe. That afternoon, the volunteer returned and gave me a packet of razor blades, which I took to Didier and Jacques. They led me outside, looking for a small stick. The razor blade was to sharpen the stick! Unable to find a suitable stick in the immediate vicinity, we went back in, and Jacques cut a small nick in the middle of my big toe and prised out the maggot. I still have the occasional shooting pain from this cut, twenty years later.

Though I was invited into all the sessions of the meeting, many were of no direct interest to my work, and so I spent some time helping the volunteers who were setting up a small bar serving the local Weiss bier for the evening. They showed me how to pour Weiss bier, gently down the side of the glass, then swirl the last few ounces around to collect the yeast and pour it quickly into the glass. I was so impressed by this, that I felt I had to invite all my Cameroonian colleagues to the bar after the evening session finished and show them the technique. They too were impressed, and we ordered fresh bottles so that each could try. We spent a very entertaining evening perfecting our technique.

After the conference, I invited the three Cameroonians into Munich for a bit of a tourist adventure before they caught their planes back to Cameroon. We went into a high ceilinged beer hall and I ordered a large stein of beer for each of us. As Didier drank, he discovered that there was the bottom of another broken glass inside his beer! I called the waiter over. He was unimpressed. He offered to replace that one beer but none of us felt like finishing our beers at this point. Without any German, and in what was now clearly a hostile environment, I was forced to pay up for three of the beers and leave. Sadly, I think this was no accident, but a disgusting racist act. It really spoiled our trip around Munich, and soon afterwards I put my friends on the bus to the airport.

When I got back to the UK, I wrote up my proposal for Jacques Ngoun and the £6,000. It seemed to me that after what I’d seen in Bipindi, Jacques would not get much value out of a satellite phone. He had nowhere to charge the battery in his village, the equipment was delicate and sensitive and would probably quickly deteriorate in the humid environment. As the problem was being able to communicate with Jacques, and vice versa, I thought there was a better solution. Instead, I proposed that Jacques get a small motorcycle which he could use for his work, and also to drive to Lolodorf each week. There I proposed he pay for a desk at Planet Survey, as well as a computer, office supplies, and one day a week’s secretarial help. This would make CODEBABIK a partner, as Jacques would be paying into Planet Surveys office costs, and have his own small budget for gasoline, telephone, secretarial help, office supplies, and the occasional trip to Yaounde, over two years, all for £6,000. This I thought would be a better use of the money. Sadly, the £6,000 was speculative and never funded, so I did not get to see how this, my first local project proposal, would have worked out.

“This acculturation seemed sad to me, but I was new and held my counsel.” So many people could not have done this. I’m curious about the maggot. Was it a bot fly larva or HOW?? Well, there are a lot of things in this post that make me curious…

Munich — on my one visit to that city I sat down in an outside restaurant in the middle of the city. The Maitre’d looked at me and picked up two menus and tried to decide between them. The only other diner was a man from Russia. Finally the maitre’d decided on the German menu. Thankfully, I could read a menu in German or I would never have had the glorious weisswurst they served there.

Anyway, reading your post and writing this made me see my latent wanderlust…

LikeLike

Martha, Thank you again for your comments. Acculturation issues are complex, and I found no easy answers. One issue though that I found easier was access to healthcare. By both driving Pygmies from the forest, initiating new disease patterns, and simultaneously denying them available healthcare, they have suffered enormously. I researched this and demonstrated that even the best-intentioned international health provider charities were not doing their job for Pygmies. Sadly, I got no funding to continue the work (I only need expenses, as I take no salary). I think the maggot was called chiggers, but my memory is not certain. I intend to follow up with another part on Jacques sometime, for the insatiably curious.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I look forward to reading it!

LikeLike