Greenpeace Daze part 6

15 minutes

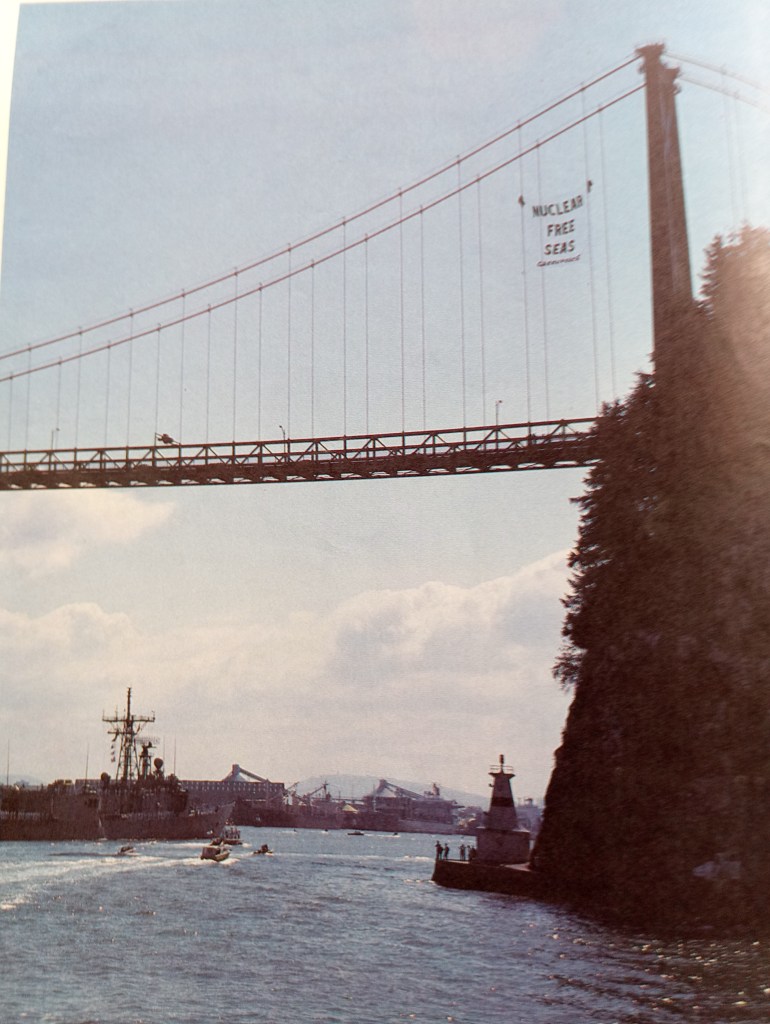

In the spring of 1987, Greenpeace launched an important new international campaign called Nuclear Free Seas. Most of the nuclear weapons in the world are carried by the world’s nuclear navies, especially the US and the USSR, but also by China the UK and France. With the majority of the warships carrying nuclear weapons, and fleets from all these navies in constant movement, there are numerous (usually unreported) accidents and the great risk of an ‘incident’ that could lead to those weapons being used. Greenpeace demanded that the world’s navies remove these dangerous and provocative weapons, and the first stage in the campaign was publicising the widespread visits by nuclear armed ships into the heart of the world’s metropolises. Jim Bohlen, Greenpeace Canada’s nuclear campaigner discovered that nuclear armed US warships would be attending SeaFest, Vancouver’s annual family event celebrating boats and boating, in July.

I had taken three months off from Greenpeace in the summer of 1987. My pal Bob was visiting from the UK, and I intended to spend a relaxing summer enjoying British Columbia’s wild places, as well as Vancouver’s music, fringe theatre and dance festivals. Then Jim asked me if I would hang a banner on the Lion’s Gate bridge, at the entrance to Vancouver’s inner harbour to protest the warships. This was right in the middle of my holiday, but I had to say yes.

We had been buffeted by the wind when we’d suspended ourselves from the Cambie street bridge the year before, even though the bridge was far lower and relatively sheltered. I felt it would be dangerous to hang off the Lions Gate bridge. The banner would have to be large to be visible hanging off the roadbed two hundred feet off the water. It would be very difficult to stop our ropes chaffing on the bridge edge, which I worried risked them breaking, and our plunging to our death. So it was necessary to climb up the bridge instead.

The Lions Gate bridge connects Vancouver to the north shore. It is a smaller version of the famous Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco, but in a more dramatic setting, soaring out of Stanley park with its giant Douglas firs, towards the north shore mountains. The main span is 1,552 ft, the towers are 364 ft high, and it has a ship’s clearance of 200 ft.

We would be climbing the first two cables to the left of the tower.

I had looked at the bridge earlier in the year, out of professional curiosity, and had told Jim I thought it possible to climb the vertical cables that connected the bridge to its giant suspension cables. To make sure, now it was more than theoretical, I went back and had another look. The vertical cables were made of braided steel and perhaps two inches in diameter. They were in pairs, and connected like a ladder. But, to stop pranksters or drunks climbing the ladder, there was a twelve foot section at the start where the rungs had been removed. I knew that the prusik knot could be used to climb a one inch nylon rope. But I didn’t know if the knot depended on compressing the rope- as it certainly wouldn’t compress a steel cable. I tested this by prusiking up a thin telephone pole support cable and it seemed to work.

If we were going up, the banner would be fixed to the vertical cables, and wouldn’t give in the wind, and I felt sure it would rip. So, I looked into using a net banner, following the lead of Jim Bohlen and Kevin McKeown’s Cruise Catcher [see Refuse the Cruise]. I went to see a fishing net maker and explained what I needed. He asked what bias I wanted, and I got a brief course in net making. He argued a net wouldn’t hang strait without some bias, but I was worried if it was too curved the slogan would not be legible. We compromised on a 15 percent curvature, and I ordered a 30 x 40 feet net of heavy duty netting. Then, in spite of the curvature, using my usual graph paper calculation to layout the slogan, I ordered five-foot high letters made out of heavy duty black vinyl. One night several canvassers helped lay out the net in the office and attached the slogan ‘Nuclear Free Seas, Greenpeace’, using plastic cable ties.

The plan was to spend the night on the bridge, to greet the warships as they sailed past in the morning, so we would need to carry up a lot of gear. The local climbing store, the marvellous Mountain Equipment Coop, had hammocks used by big wall climbers. Unlike the usual hammock that is tied between two trees, these hammocks are attached to a single point. I bought two, and began practising how to set one up when suspended in mid air.

I found setting up the hammock was not easy when I hanging from a roof beam on my back porch. It was quite a manoeuvre to get in and out, and I spent a long Sunday afternoon getting the hang of it.

We had to carry all the equipment we’d need for spending 24 hours on the bridge. We’d need a large backpack with our hammock, a sleeping bag, food, water, warm clothing, and spare climbing gear. All, our gear would probably be confiscated, so I didn’t want to use my own camping gear, as I was planning on going camping a few days later. I bought sleeping bags, backpacks, water bottles, new climbing gear and other kit. We were also going to use a newfangled device, a mobile phone, to keep in touch with the office and take press calls as we hung in our hammocks. I had never used a mobile phone before. It was massive, and each battery weighed about a kilo, and I had to carry a spare as they didn’t last anything like as long as a phone battery on a smart phone nowadays.

I also needed a safe and trustworthy partner. This was going to be a difficult and potentially dangerous action. We’d be high up and blasted by any wind or rain, and could not afford to make any errors. Bill Gardiner was not a climber, but had already done at least one climbing action with Kevin McKeown, the Vancouver action coordinator. Bill volunteered, in spite of the extra complications, and risks, of the height and wind, and setting up and sleeping in a hammock. We would need to have a number of training sessions, both to refresh Bill’s basic climbing skills and to practice prusiking with a large backpack and setting up and sleeping in a hammock. Bill was right in the middle of his masters degree and hard to get hold of. I was worried when he missed two of our planned training sessions due to deadlines for his M.A. Perhaps because I was still officially on holiday, and had a friend over from the UK, I left dealing with this until rather late. Finally, the morning before the action, I arrived at his house and roused him from an all night study session. After just a couple of hours, Bill had had enough, and left to catch up on his sleep. This put me in a real quandary. Bill had not really had adequate training, and I ought to call the action off- as it was far too late to find a replacement. But Bill was dedicated and determined, and I thought of the first Greenpeacers going off to Alaska to stop nuclear testing. Each of us makes our own decisions about the risks we are prepared to take. Bill had made his. He promised he’d practice using the hammock at home, and so I dropped him back home with his kit and made a silent prayer for our safety to the god of good causes.

I had been avoiding the office as I was still officially on holiday, so the campaigners were not aware of these last minute problems. I was ready, the kit was ready, Greenpeace was all set up to support a major action, and Bill promised to take a break from studying and practice some more that evening. I arranged to pick him up at nine the next morning.

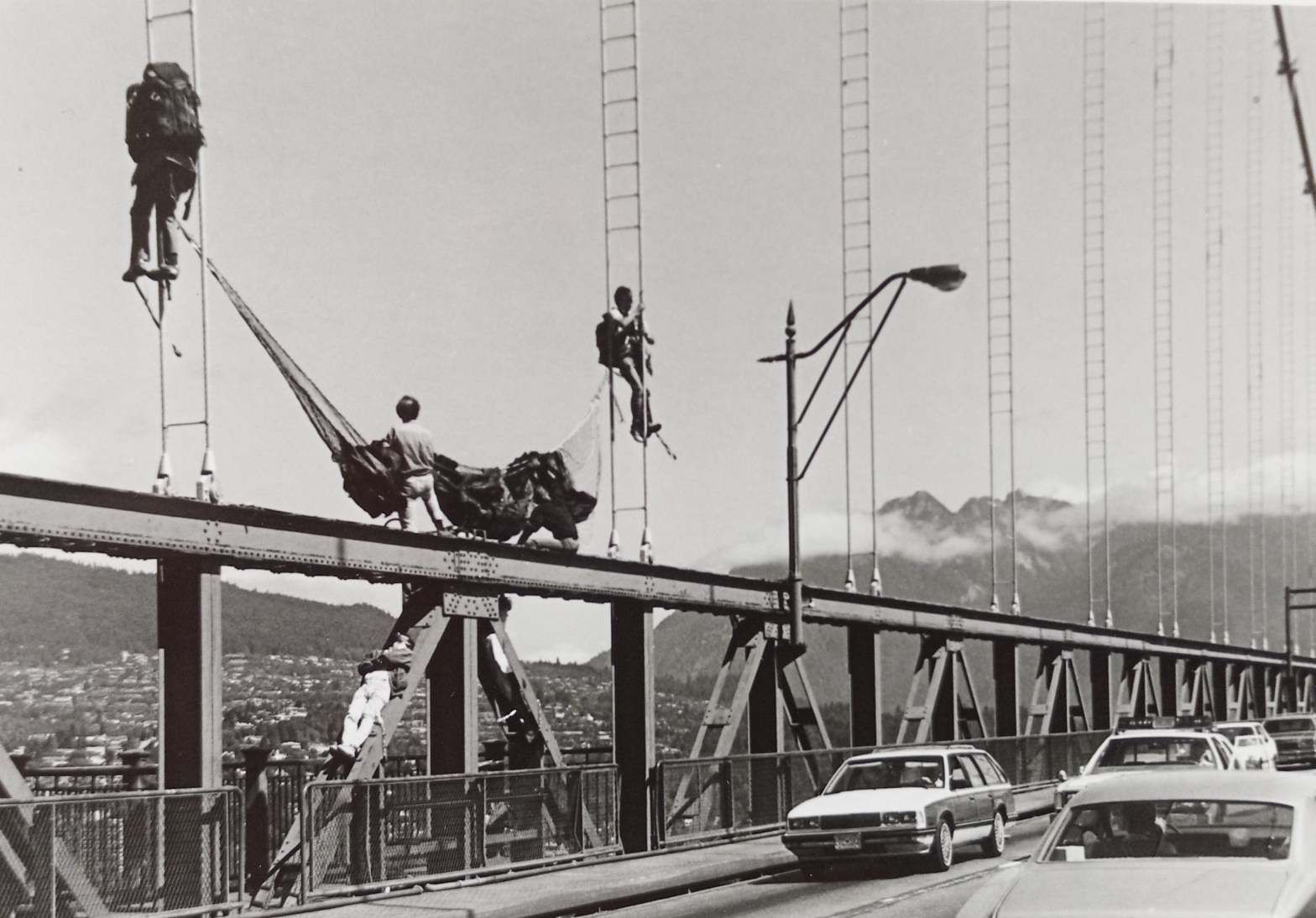

We drove to the Lion’s Gate lookout car park, where Kevin had assembled a team of helpers, went over the final details and waited for the ‘go’. Bill looked exhausted from too many all night study sessions, but said he was fine. He is bigger, younger and tougher than me, so I had to hope he was right. We put on our packs, and then slipped a couple of spare slings over our neck and shoulder, ready to go. There was a delay, and we took the packs off and rested until we got the ‘ok!’ on the radio from our scout on the bridge. It was just a few hundred yards down a flight of steps and along the pavement to the small balcony which protruded from the side of the bridge tower two hundred feet above the water. We were going to go up the first two sets of cables past the first tower. The cables started on a narrow beam ten feet above the roadway. Bill got onto the beam with his helper, and attached himself to the cable he was going to climb, and I did the same. My friend Bob had offered to risk arrest and be my helper for the day.

The beam was ten feet above the road, but on the other side the drop off was two hundred feet, a potentially fatal fall into the turbulent waters of the First Narrows. The banner was stretched out between us along the beam, as it was too big and too heavy for one person to carry in a pack with all the other kit we needed. At this point in the action, we were vulnerable to anyone grabbing the banner from the roadway. Though this would be a risky manoeuvre for them, as they would need a leg up in a very exposed and precarious situation. Unless they found a ladder. Fortunately, the Vancouver police behaved sensibly, focussing on closing the middle lane and directing the traffic.

But the action was at a critical point, and we had to move fast.

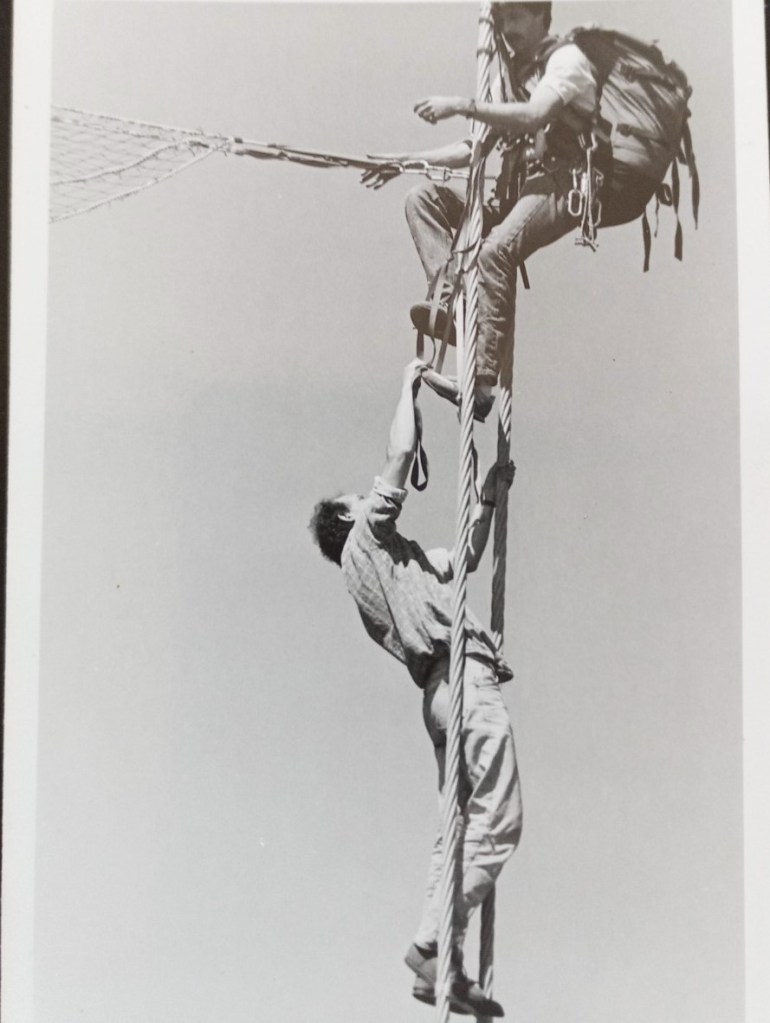

I attached my prusiks and prusiked up the twelve feet to where the rungs began. There I realised I couldn’t make the step up from a sling at knee height onto the first step of the ladder at chest height carrying a forty pound backpack. I had to make some intermediate steps. I took one of the slings off my shoulder and looped it onto the first rung of the ladder. I was still unable get my foot in this sling with the backpack pulling me backwards. By using the other sling, and my spare prussic I made another step and using these two extra steps, I got my foot onto the first rung of the ladder, my arms exhausted with the effort. After clipping into two higher rungs with safety slings, I looked over at Bill, and I could see that he had the same problem. I shouted to him to make a couple of steps with his spare slings. But when he had put his pack back on, after we were delayed, he had put it over his slings! I watched as he tried several times to haul himself up without extra steps, but with the weight of the pack and pulled by the banner, he slumped back. Bob was near the middle of the beam holding the banner up to stop it dropping further towards the road and the police. I didn’t want to alert the police that we were having difficulties, as they might feel obliged to interfere and stop us. I called Bob over, and told him, as discreetly as possible, that what he had to do was critical, and dropped two slings to him, which fortunately he caught.

He walked insouciantly half way over the beam, to pass the slings to Bill’s helper. Understandably, given the exposure, Bill’s helper was clinging to the beam, and was not able to take the slings. Then, in the most astonishing act of daring, Bob stepped over him, poised above the deadly 200 foot drop, and walked the rest of the way across the beam, and then stood on tip toe and passed the slings up to Bill. This was the critical moment. Without this act of bravery, we’d have been in serious trouble.

Bill, tied a sling onto the first rung of the ladder and stepped into it, another step and with an enormous effort, he pulled up onto the ladder, where he stopped completely beat. I went up as far as the banner between us would allow, and now the banner was out of reach, Whew.

After we had both had a chance to recover, we carried on up the ladders and stopped a hundred or so feet above the road. We slung our backpacks onto the cable, and then much relieved to be free of their weight, attached the top of the banner to the cable and then climbed down the ladder forty some feet to set the bottom corners. As the banner filled in the wind, I could feel the force pull painfully on my harness. It required all my strength to heave the banner line and attach it to the ladder and get the weight off my harness. The banner ballooned out, looking magnificent in the wind. We’d done it. We climbed back up the ladder to arrange our hammocks near the top of the banner, and climb in. The view was exceptional, but it was early afternoon and we had press calls to deal with.

Next: First night in a hammock, and media interviews from my aerie.

Dedicated to two heroes Bill Gardiner, who braved 24 hours, 300 feet above the water, having missed much of the vital training, and Bob Stafford who stepped up at a critical moment and saved the day. Without their bravery, this would not have been possible.

Thank you. I hope you enjoy reading other stories too. I especially recommend Market Research Madness, and the completely different Slapstick, which makes me laugh.

LikeLike

Your blog is amazing 🙂

LikeLike