Two climbs on Popocatepetl

20 minutes

No man ever steps into the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he is not the same man- Heraclitus.

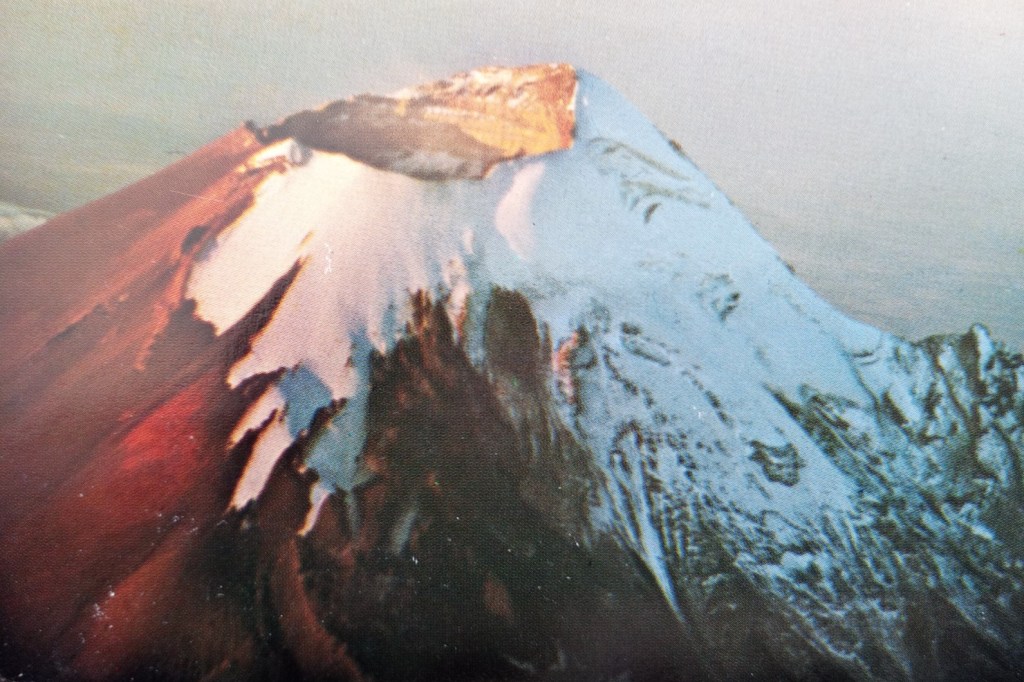

Twice a day, Pablo’s donkey passed Francisco’s place in San Pedro barrio, Tepoztlan, carrying jerry cans of pulque, Mexico’s cactus beer. Francisco’s shack was right on the edge of Tepoztlan near the last remaining agave field in the town of the god of pulque. Pablo would call out as he passed the shack, and we would often buy a litre or two of the milky liquid. One afternoon Carlos, a traveller from Spain, and I took a couple of litres of pulque up the hill behind Francisco’s shack and sat with a view of the great volcano Popocatepetl (5452m), visible in the distance over the intervening hills. As we drained the last of the pulque, Popo’s summit snowfield glinting in the afternoon light, we concocted a plan to climb Popo a few days later, on New Year’s Eve.

Popocatepetl is high enough, that in spite of being in the tropics, the top can be bitterly cold in the winter. I had a warm sleeping bag, for a night in a hut, and managed to borrow a down jacket, warm mitts and a wool hat from Texican friends who would soon be returning to the freezing US winter. Carlos was less lucky, but found an old leather motorcycling jacket and lined leather gloves. We set off on the 29th December, taking several local buses to Amecameca, where we could hire ice-axes and crampons. The equipment we were offered was old, and dilapidated, but it was only a long slog up volcanic ash and snow after all. The next day, we left Amecameca and hitched the road that climbs steeply up to the Paso des Cortes, (3400m) the saddle between Popo and Iztaccihuatl (5286m) the sleeping woman.

From the pass, which Cortez had used to advance on Mexico city, we were lucky to get a ride the three or so miles through the alpine forest to Tlamacas, (3947m); where there is a large climbers chalet, with a canteen and bunkhouse. Popocatepetl is Nahuatl [the language of the Aztecs] for Smoking Mountain; it is the second highest peak in Mexico, after Pico de Orizaba or Citlateptl (5,700m). It looms over Mexico city and it is still intermittently active. We got to Tlamacas early enough to continue to a mountain hut a couple of km further on and about 200m ft higher. The hut was small, without any furniture and crowded with a dozen students from Mexico City, some of whom were passing a bottle of Tequila. We found space for our sleeping bags on the plank floor and ate a cold supper. Just before dark, someone ran into the hut to report that a climber had fallen high on the mountain and was injured, then carried on down to alert the mountain rescue. An hour or so later, a group arrived carrying the injured climber. I learned from his girl-friend that he was an experienced climber from Colorado, and had slipped on the icy summit slopes, tumbled over volcanic rocks and broken his leg. I offered my sleeping bag for him and encouraged his girl friend to get in with him to keep him warm as it was now nearly freezing and he was suffering from shock. When the mountain rescue team arrived with a stretcher, they had brought a cheap, thin kapok sleeping bag, with an all round zip. I worried about the injured climber staying warm on the long carry down in the dark and offered them my sleeping bag to keep him warm, in exchange for the miserable rescue bag.

After the mountain rescue left, the students finished off their bottle of tequila and put out their lantern. I had a long, bitterly cold, and largely sleepless night in spite of my down jacket. Carlos and I woke to our alarms before dawn. The wind was very strong, and buffeting the hut, but we had heard that this was normal, and it usually moderated later in the morning. We set out at first light, the first, and it turned out the only party to attempt the summit that morning. The climb was reasonably easy up 30 degree slopes on hard snow, and soon the wind died down. We felt the altitude, but had the advantage of having spent over a month at about 1700m in Tepoztlan, where we did a lot of walking including, sometimes twice a day, the 2km climb up the steep hill from town to Francisco’s shack in the San Pedro barrio.

We arrived at the craters edge into a blast of freezing wind and were surprised to find four people waking up from a bivouac. Behind them the crater dropped hundreds of metres into a sulphurous pit where mist swirled. The group of four well-equipped Mexican climbers, in full down suits, had come up late the evening before and spent the night bivouacked on the craters lip. They were getting up and kitting up to climb to the summit, on the far side of the crater. The wind was suddenly tremendous, and bitingly cold and they decided that it was too dangerous to climb along the crater edge to the summit. As we talked to them, I began to get very cold. I looked at the slope back down. The wind had turned the snow crust to ice, which glittered in the morning sun, and I was not confident I could climb down safely with crampons, which I hadn’t used since learning to use them ten years earlier. I was also worried about my ability to balance on the steep ice as I was beginning to get really cold and becoming hypothermic. I felt it only too likely I’d trip over my crampons, and start to tumble. I feared I’d end up like the Coloradan climber, or worse.

Thankfully, the Mexican climbers decided to rope down the slope, and offered to tie us on too. So we slowly down-climbed on belay, and then sat with ice-axe wedged waiting for the rest of the party. Carlos was now getting seriously hypothermic with only a motorcycle jacket in the sub-zero temperature and strong wind, and I worried he’d lose the ability to climb. I was bitterly cold too, sitting shivering in the snow, in spite of the down jacket. At one point, I contemplated untying and descending alone to get moving, as I became colder and colder. I sat numbly looking at the fantastic views across Mexico almost to the sea. Eventually, after two or three very slow rope lengths, belaying six people down one by one, the slope eased and we untied. We’d been very lucky to have met up with the Mexicans and thanked them profusely. Then we all ran whooping and hollering down the rest of the snow and plodded back on the volcanic ash path to Tlamacas, and warmed up with hot drinks and food. It is only in writing this piece that I remember how close we were to not making it down safely.

The next day, we returned our rented equipment in Amecameca and I went to find the mountain rescue and my sleeping bag. There I heard the good news that the Coloradan climber was safe in hospital, and swapped their very poor sleeping bag for my own. This was my second time at 5,000 metres, but like the first time in the Himalayas, it was a ridge line not an actual summit. I felt that I’d climbed Popo, as I had looked into the crater, but none the less, I had wanted to go to the summit.

Over the next few years, I climbed half a dozen non-technical volcanoes in Mexico and Guatemala, each one a thrilling experience, some with exciting volcanic activity. I was back in Mexico one winter in the early 90s, again staying in Tepoztlan, but now in a posher house in the flatlands south of el Mercado. Francisco and his Texican friends had purchased the pulque fields to save a small piece of the traditional economy. So, I was treated to some fine pulque for old time’s sake and, inevitably, decided to have another go at Popo.

This time I went alone. I got a bus up to the Paso del Cortes, and was dropped off on the saddle, and walked the three gently climbing miles to Tlamacas, with lovely views of pines and other alpine plants. It was a sunny winters afternoon, and I had time to wander into the meadows to look at the wild flowers, and sit under a pine listening to the mountain birdsong.

I spent the night in the climbers hostel, and got up at 4 am with the first group heading off for the summit. We walked along with headlamps lighting a black sand path in the mist. I chatted to various groups as we stopped for breathers in the cold, windless air, but it didn’t take long for the majority of the other climbers to overtake me. Most of them were college students from Mexico City, over 2200m, and even the Americans studying there for a few months had had a good acclimatisation. I was fairly fresh from Vancouver, at sea level, and I was also over 40, and not particularly fit.

It got light as we arrived at the snow, a steep and rather icy slope leading to the summit, and I was back with the slow coaches. A dozen or so people were visible a hundred or two metres above us, going up the long snow slope to the summit. Many of the slower hikers looked at the steep snow slope and gave up. I kicked steps about 50 metres up the snow, and sat on a flat rock to put on my crampons and to get back my breath. The altitude was making breathing painful and I felt terrible. I was joined on the rock by a Mexican woman of about my age.

After about 10 minutes, I realised I was beat and gave up on my ambition to get to the top. Instead, I descended and showed six or eight people who had stopped below the snow how to use their ice-axe and to walk up and (importantly, from my own experience) back down the slope in crampons. I spent an hour doing this, and one by one my students picked up the technique, took heart, and went on up the slope towards the skyline. I then returned to the rock for my pack. The Mexican woman was still resting, but she now decided to carry on up. I went up with her, but it wasn’t long before she was going faster than me, and disappeared into the distance. I was left to puff up, last and alone. When I got to the craters edge, about twenty people were lying in the sunshine, nibbling on snacks or taking pictures. I lay down for twenty minutes, to recover my breath, and soon afterwards they all left, moving off along the rim to the left for an easier snow-free descent. After my rest, I decided I should go for the top, and was surprised to discover it was several hundred metres around the rim. Feeling lonelier and lonelier, I walked through a swirling mist of sulphurous fumes with views to the vast crater floor hundreds of metres below, and with a stiff climb at the end to the actual summit. Whoopee, I’d finally made a 5,000 metre summit. The views from the summit were extraordinary, from Mexico city to the east, past Puebla in the west, to the distant cone of Citlateptl, more than a 100 km away. But I was alone, and nervous of the swirling fumes, so I didn’t stay long and descended past our resting place and around to the descent. I plunged down, ploughing through deep black ash and sand, though it was quickly more tiring than I’d expected, and I was soon exhausted. I carried on straight down, rather than angling back towards the ascent route, as I should have, so at the end of the descent I had a several hour walk back around the mountain. There was terrific heat off the black volcanic sand, in the noonday sun and I had to take numerous rests, dehydrated and breathing painfully at over 4,000 metres. It took me several hours to get to the trail down to Tlamacas. I arrived exhausted, and decided to spend another night.

Man is most nearly himself when he achieves the seriousness of a child at play -Heraclitus

After a siesta and a good meal in the cafeteria, I spent the evening chatting to the arrivals for the next day’s attempts. Again, most were Mexican students but many of them were Americans studying in Mexico City. There were also a few climbers: two thirty something Brits and three fifty something Americans who had recently climbed Denali, North America’s highest peak. I was woken by everyone leaving between four and five am but went contentedly back to sleep. Around eight, the Americans returned having failed on their attempts due to altitude sickness. Later, the two Brits came back also unsuccessful. I thought it ironic that more or less any half motivated student could get up the mountain, but that it had defeated five good but unacclimatised climbers. I was lucky I’d stopped and helped the stragglers the day before, or I too would have given up. It was a lesson in the value of resting when suffering from the altitude.

No one ever climbs the same mountain twice, for it is not the same mountain, and you are not the same person. If something as solid and unchanging as a mountain is never the same, due to ever changing conditions, how much more so is it with life. Each of us faces the same, so different world.

Recently, Popo is off limits due to volcanic activity.

Some pictures of the 2019 eruptions

https://www.volcanoadventures.com/tours/volcano-eruption-special/popo.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fshQ_q7k9h4 a YouTube video of recent skiing action that shows there are a number of serious hazards on Popo.

Is a good guide to the three big volcanoes

http://www.peakbagger.com/climber/ascent.aspx?aid=1228

Is an interesting traveller’s tale of a climb on Popo

As you can see you need to take the risks seriously. I was very lucky, don’t count on being so fortunate.

Hey Simon!

It has been 40 years since a summer in Vieux Québec in a demi sous-sol on Rue Ferland.

Please get in touch with this Yank at marcs at cinci.rr.com

I’d love to catch up. You’ve been busy!

LikeLike

Love it, Simon!

LikeLike

Wow! Better and better.

Wonderfully descriptive of setting, situation, and agency in action.

You share a bigger story with your intimate story; and it so well underpinned by the philosophical quotes and, not least, your reflections on the adventure.

A pleasure to read –

Gary.

LikeLike