Stopping Canada buying nuclear submarines

In the middle of the summer of 1988, I got an urgent call to go to the Greenpeace Toronto office to meet with Steve Shallhorn Canada’s Nuclear Free Seas campaigner. Steve got straight to the point: he wanted me to plan an action in Ottawa in a few weeks. I told him that I was extremely busy, and didn’t have a moment to spare. Steve asked for ten minutes to lay out the case.

Canada’s Conservative government was proposing to buy 10-12 nuclear-powered submarines for what they said would be eight billion dollars, though it was widely believed it would actually cost over 30 billion dollars. There was opposition in parliament and from unions, the peace, women’s, and environmental movements. A majority of Canadians were against the plan, but the Conservatives had a large majority and could get the legislation through easily. Steve believed that the Conservatives would announce whether they would buy British or French submarines in the next few weeks. Discussion of the issue had disappeared from the media. Once the decision was announced, protest would be too late. Steve wanted to embarrass the government just before they announced their choice of which submarine by hanging a banner on Canada’s Department of National Defence (DND) in Ottawa. This would bring the issue back onto the front pages while there was still a chance to change the outcome. Steve had visited the DND, and spotted a pair of wide tracks going up the building. He asked me to go and see if they were climbable. The issue was so important that I had to say “Yes.”

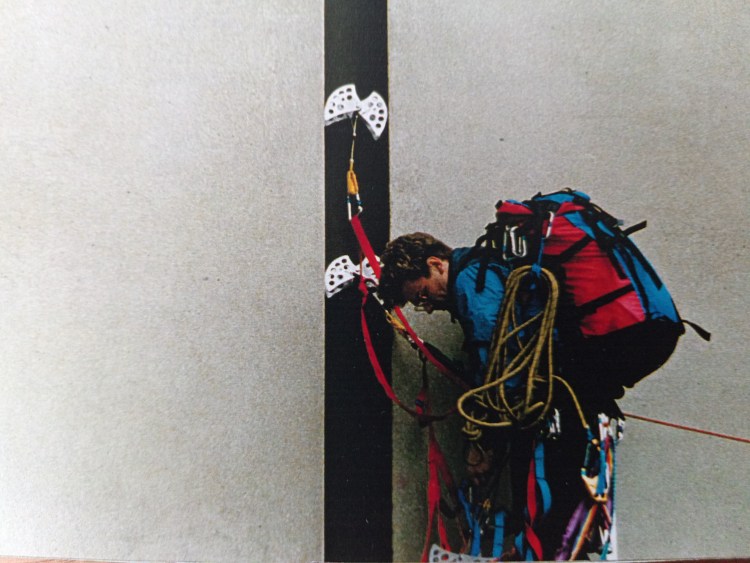

A few days later, I drove to Ottawa to look at the DND. There was a tall concrete tower on one side of a busy road and a shorter block on the other side. They were connected so that the road went underneath the middle of the building. On either side of the road, a shallow but wide crack climbed up the side of the building. If we could climb these cracks, we could hang a banner across the road. I measured both cracks, they were 8 inches wide and about 4 inches deep. I had never seen any climbing equipment big enough to fit, but there are pieces of equipment used by rock climbers called cams that fit into cracks and expand on a spring. They are strong enough to hold a falling climber, and would surely work here. However, as far as I knew, they were only made to fit cracks up to three or four inches wide. If we could get a manufacturer to make us cams for these much larger cracks it should be possible to climb the building. Cams are strongest when compressed under tension, so we would need about 10 inch cams- which would be enormous and quite heavy.

I would have to be one of the two climbers, as we were short of trained volunteers. The second climber also had to be a Canadian as it wouldn’t be appropriate to have an American protesting Canada getting nuclear submarines. The only Canadian climber available was Spider, who was a great guy, but a beginner. This climb was tricky and going to need the focus and skill of an experienced climber. A lot had to be done in a couple of weeks, and I was already working flat out.

A Greenpeace climber from the US offered to help by ordering the six bespoke camming devices from a company in Oregon, I thanked him and gave him the measurements of the crack. I discovered that another piece of large equipment (the Big Bro) already existed . I hoped they would be effective to hang the banner on, and though I’d never seen one, I ordered four from the Mountain Equipment Coop in Vancouver by mail order. However, there was still a real difficulty as I hadn’t found a climber to accompany me on the climb. Then I remembered a Quebecois climber I had met a month earlier on a day off at Mt Tremblant, a climbing area north of Montreal. He’d asked me what I was up to as I trained Spider in the basics of climbing a rope and I explained we were about to start a full summer of actions in Quebec and Ontario. Nelson had said casually that he’d be interested in doing something sometime with Greenpeace, and I’d taken his number. He was my only hope, so I called him:

‘Hi, Nelson, it’s Simon. Remember we met last month at Mt Tremblant?” Fortunately, he did.

“I have something coming up and need a climber. Are you free next week?” Fortunately, he was.

“It’ll take a few days to train and prepare, are you free for four days?”

“What is it for?”

“I can’t tell you over the phone”.

Nelson agreed provisionally, and we planned to meet in Ottawa in a week.

I carried on with my day job of organizing a series of actions around the Greenpeace ship Beluga boat tour and then spent every spare moment planning for this action. As I was on the road, I couldn’t use a Greenpeace office credit card to pay for expenses, so everything went onto my personal card. I had to order the banners, arrange for them to be lettered, sort out delivery to the Ottawa office, and talk to the canvass coordinator to request help from the canvassers as a local support team. The Ottawa office also arranged van hire, ladder hire, and other equipment. Steve sorted our hotels, and took up a lot of slack. I heard no news from the Greenpeace climber about the critical giant cams and began to get worried. I tried to track him down, but couldn’t contact him. This got serious as the action was approaching, and I didn’t have the necessary equipment. I called the company making the cams, but it took a number of calls to find anyone who had heard of the order. I was on the road, so no one could call me back, and I had to make many of the phone calls from coin boxes in gas stations. By the time I got to my motel at night, offices and factories were shut. When I did get through to someone who knew about the cams, they had not been told how urgent they were. They said they’d try to get them ready on time. I told him I was from Greenpeace, and that “something important” depended on them being with me in five days. He said he’d see what he could do. There was also a hold-up in the delivery of the Big Bros. I needed all these things. It was touch and go. If one of the key components was missing, we’d have to call off the action.

When Nelson got to Ottawa and I told him the plan was to climb the Department of National Defence. He was shocked. Not surprisingly, he thought we’d get into serious trouble. This was an enormous step for him from making a general offer to help us sometime, to climbing the belly of the beast. For a while, it seemed as if I might need to scramble for another climber or call the action off, but after some thought, Nelson very bravely agreed to join me as the second climber. We spent half a day together going over the details of the climb, and how to deploy the banner. As he was a lot younger than me, and very fit, I got him to carry the banner on the day. In case we couldn’t get that large banner out for some reason, I had another, smaller banner in my backpack. Neither the cams nor the Big Bros had arrived and I spent some time on the phone chivvying my suppliers and getting them air freighted. There were now a number of things that could go wrong. After getting assurances that the two kinds of specialist climbing equipment would be airfreighted, I had to make sure that everything else would work.

Fortunately, Ottawa had a full-time door-to-door canvass operation. When I arrived in Ottawa, I had met the canvassers in the afternoon before they went out canvassing, and recruited most of them as volunteers. The next morning we had a thorough briefing. I had asked the Ottawa office to rent two 26 foot extension ladders. If we started climbing from road level, it would take several minutes to get above the reach of security, and that was too long to risk. I explained to the ladder team their key role. The most critical time in the whole action was going to be getting very quickly off the ground and too high to grab. The height you need to get to be safe is more than you might think as they might have a step ladder- or certainly a chair close by. Even when we climbers were out of reach, the rope we needed to connect us- which we’d use to pull the banner across, would inevitably sag lower. I felt we had to get 20 feet off the ground very quickly to be safe. The ladder crew’s speed and efficiency would be key to the success of the action.

The plan was to drive up in a van, stop just before the tunnel, block the road, and run a rope across to join me to Nelson. At the same time, two teams would each pull a ladder off the roof of the van and set it up by a crack. With the ladders held securely, Nelson and I would climb up, stick our camming devices into the cracks, and clip in (connect ourselves to the camming devices). Once we got our weight off the ladder and onto the cams, the ladders could be removed, collapsed, and put onto the roof of the van, and the van would drive off leaving us unreachable. Until the ladders had been driven away, they could be used to come after us. It was critical how quickly we could get from stopping the van, to deploying the ladders, to getting up the ladders and attached to the building, to getting the ladders out of there.

Two nights before the action, after the canvass had finished working for the night, the two ladder crews of three people each, with their ladders, the road crew, Nelson, and I set off in a canvass van with the seats taken out. We drove around the outskirts of Ottawa looking for a place to practice and settled on a large, blank, thirty-foot high wall in a housing development. We swung into action. The van pulled up to a stop, and the two ladder crews jumped out, dragged out the ladders, and set them up twenty feet apart. Two of the road crew role-played blocking the road, and the third connected a thin cord- the banner pull line, to me and ran across to Nelson and clipped it onto him too. Nelson and I clambered up to the top of the ladders wearing our packs stuffed with various heavy items. This took far too long. We returned to the van for a discussion on what had to be done more quickly, and after circling the block, we tried again and cut the time in half. Another chat to see how we could make it really smooth and we did a third and very efficient deployment. Our late-night ladder antics caused surprise to several people coming out of the building.

The cams arrived the day before the action was planned to take place. It was very worrying that they weren’t big enough. They were barely 8 ¼ inches which was an insufficient margin for an 8-inch crack. This was a real blow. The one piece of equipment we had to fix ourselves to the building was borderline, and could potentially pull out, dumping us on the concrete below. I really hoped they’d work. We also had the Big Bros, they expanded to 10-12 inches and seemed they’d do a good job holding the banner. Nelson and I played around with the equipment in the hotel room, but we didn’t have the time to find somewhere to test them.

On the morning of the action, there was a delay as there appeared to be an increased security presence at the DND, and Nelson and I sat in our hotel room, all kitted up with harnesses on, waiting for a ‘go’ from the scouts near the DND. Not having a set start time adds to the nerve-wracking nature of an action. We were doing a really important action, with a climber brand new to Greenpeace, a new crew, equipment we had not had a chance to practice with, and a very low tolerance for the critical cams which would hold us as we climbed high above a concrete pavement. There was too much to go wrong, and no time to make things safer. On principle, I should have called the action off. But the issue was too important, and we would have to deal with any problems as they came up.

Eventually, we got the word and drove in the van to the DND and stopped just before the tunnel. As Nelson and I jumped out and put on our backpacks, a helper connected a rope between us and Nelson crossed in front of the stopped traffic to his place below the far crack. The two ladder crews were brilliant. They had the ladders up in seconds and both Nelson and I were climbing up towards the top of the extended ladders, carrying large backpacks, with three vast cams, and two Big Bros swinging from our harnesses. Behind us, a GP helper in an orange high-viz jacket and safety helmet held up the traffic with a stop sign. A second canvasser in the traffic crew walked down the row of stopped cars and reassured the motorists: ‘We’ll just be a few minutes. One of the stopped cars was being driven by an army captain on his way to a meeting at the DND. ‘We’ll have the traffic moving in a minute or so, sir’, the canvasser told the captain.

I scurried up my ladder until I had my hands on the top rung and reached for the camming devices attached to my harness. I placed two devices into the crack, to discover that they were not only just barely big enough to fit the width of the crack, as I already knew, they were also too deep for the crack and half the nearside edge of the cam stuck out from the wall. With some fiddling, the cams barely caught on the sides of the crack. I now had to put my weight onto the camming devices 20 feet off the ground, a difficult moment given the poor tolerances, and my uncertainty the devices would hold. As the more experienced, and the person ultimately responsible, I had to test the equipment and make sure it would hold before expecting Nelson to put his safety on the line. I didn’t have time to think about what he must be going through.

I weighted one foot, the other still on the ladder, the cam held. I reluctantly bounced gently up and down, the cam still held. I weighted the other cam and when I was reasonably sure it would hold (I had to move fast and take the risk) I put my weight onto both cams and let go of the ladder and shouted down for it to be taken away. Across the road, Nelson was also having difficulty with his devices and was still on the ladder. I placed the third cam and moved the top cam up and weighted it. What seemed like an age later (but was probably just another minute or so), Nelson left the ladder and it too was taken down. The ladder crews slid the ladders down, loaded them onto the top of the van, and took off with an unnecessary, but dramatic, squeal of tires leaving us safe and unreachable above. Traffic began to flow underneath us as we began to methodically climb the crack. I looked over at Nelson, who was understandably moving carefully, and after a long pause, I saw a security guard come out of the building. The Greenpeace ground support and campaigner assured him all was well, and he stood around looking bemused, speaking into his radio. Another person, this time wearing a military uniform, came out of the building looked at the scene, and rushed off back into the building. I continued up the wall with a few delicate moments where some variations in the depths of the crack meant that cams stuck further out, and the front part of the cam barely touched the side of the crack. This meant only half the cam was operating as designed, and the cam was liable to pivot, potentially pulling out. After about ten minutes of tentatively sliding the cams up the crack and changing our weight from cam to cam, I was still a little fearful we might be dragged off by the wind, and plunge onto the concrete below.

I chatted to Steve by walkie-talkie and we agreed there was no need in going further up the building for a more dramatic effect. I stopped at about sixty feet up, already too high for a fall, and we were ready to deploy the banner. By now, the media, who had been informed we were up to something- but kept in a staging area a short distance away, were in place, cameras at the ready. I set my second device, a Big Bro just above my head to hold the top of the banner. This was a piece of equipment unlike anything either Nelson or I had ever used, that utilized a sprung tube to put pressure on both sides of the crack. It was important that the banner was held by something separate from our cams. As, if the banner caught the wind, there would be forces on the Big Bros for which they had not been designed. If they failed and the banner tore out of the wall, we could let it go. We didn’t want it to be attached to us, if it blew to the ground.

Nelson and I were communicating with cheap walkie-talkie headsets. He was dealing with the situation with aplomb, though we were very much in the hands of unknown gods. I don’t think the calculation had been made as to how big a banner, or in what wind conditions a Big Bro would hold. Once you realize that there is nothing you can do about a problem, it is pointless to worry further. However, it was important to remain vigilant. Every move of the cams had to be done with attention to get the most surface in contact with the crack side.

I set a prussic (a knot that attaches a rope to another easily) on the cord connecting me to Nelson, to hold the cord in case I lost control of it in the wind. He tied his end of the banner to the Big Bro above his head and my end to the cord that connected us. I looked again at the Big Bro to see if it was well seated, and would take the strain of pulling over the banner. I had fiddled with it as I put it in, the first time I’d ever used one. I hoped I’d put it in the right way… I had never done an action with so many imponderables and it did not feel good. I gave the go-ahead to Nelson and pulled the banner and it came slowly across, catching the wind. I felt the entire system lurch. Fortunately, it held, and the banner filled, displaying the message “Nuclear Subs, Deep Trouble, Greenpeace”. When the banner was all the way across and tied off, Nelson and I descended the crack to set the lower corners of the banner about forty feet off the ground. With the banner successfully in place, we hung in our harnesses just below the banner and awaited developments.

Soon, a fire service ladder truck arrived. After a little discussion on the ground their ladder was extended and a fireman brought his platform close to Nelson. We had decided that we wanted to climb back down the crack, for safety reasons and to display that we were in control. I presume Nelson declined a ride down, and the fireman’s ladder moved across to the banner and the fireman on the top of the ladder cut the banner down. With the banner gone, Nelson began to slowly descend the crack towards the distant ground. This took him longer than climbing up, as descending is slower than ascending, and he had an extra twenty feet to go. As Nelson descended, I attached the top of the second banner to a Big Bro and pulled the banner out of my backpack. I didn’t have much time with a ladder already deployed. The new banner was weighted with a aluminium spreader at the bottom and I lowered it to its full length of twenty-five feet. There it began to swing in the wind and disappeared under the bridge between the two buildings. I heard it bang against a set of windows lining a corridor underneath the tunnel. This corridor was filled with DND staff watching the action in their lunch hour. It would not be good if the windows broke, hurling broken glass over the DND staff, but I left the banner out for a short while so that it could be photographed, before a fireman grabbed the rope trailing off the banner bottom. This controlled the banner, and for a while the fireman unwittingly (?) helped display the banner to full effect, and the slogan “SUBstantial Waste” was clearly legible.

Soon afterwards, I began to climb down too. I was met at the bottom by a couple of Ottawa police officers who escorted me to a police car and off to the police station. As Nelson and I were being booked, the television behind the booking sergeant was showing the action as the top story on the 4 o’clock news. The booking sergeant kindly put up the volume and we all, arrestees and arresting officers stopped and watched the news together. Everyone was polite and friendly.

Afterwards, Nelson and I were put into a cell for an hour or so, before being escorted to a room where we were asked by two detectives to sign for the equipment they were returning to us. I insisted on a thorough inventory, both of the equipment confiscated by the police, and that returned to Nelson and me. Then I insisted on making a copy for me to take away. This took an hour or so, to the irritation of the detectives, who wanted to get home, but it was essential to me that I had a record for my inventory control and to make sure we got back the goods confiscated.

When we got out, around six o’clock, we went back to the hotel and out for a celebratory meal and a few drinks. Everyone was on a high. We’d pulled off an action on the Department of National Defence, in the nation’s capital, and gotten both banners up and properly deployed. The coverage was staggering, as the story was at the top of the news on every channel and included several segments: the banner beautifully displayed on the DND, interviews with the campaigner Steve Shallhorn, (or a French campaigner on CBC francais), questions to the Minister of Defence caught in the corridors of parliament (who said wittily that “I am glad to see that Greenpeace has become attached to the DND”). On several stations, vast ugly nuclear submarines were shown, and the question of whether Canada needed them was asked again. The news reporters took a rather ironic tone, lauding Greenpeace for pulling off a bold action on the DND. It was the cause celebre and nuclear submarines were back in the news, with a review of whether they were a good idea. The government looked appropriately foolish and unprepared. We couldn’t have asked for more.

The Ottawa canvassers who had provided most of the volunteer help as ladder crew and traffic control were over the moon. There were not a lot of actions in Ottawa, and nothing before on this scale. They’d had a critical part in the success of the action so they were in a great mood. I felt an enormous relief. All actions have risks; risks of accident and risks of being stopped. Carrying out an action in broad daylight, on a busy road, on a high-security building, with a largely new crew and an untrained climber new to Greenpeace, and untried faulty equipment offered many opportunities for failure. Everyone was brilliant, and I had to hand it to Nelson, the real star of the show, for taking on a high profile, potentially, and to be realistic actually, dangerous action, with possibly serious legal consequences for the climbers. He’d had no warning, or opportunity to prepare himself psychologically for the stress and had come through with flying colours. He’d even made a good sound bite to the cameras as he got down to the ground.

The action continued as top of every news show that night, on all the TV channels, and was front page the next day in the Ottawa papers. Questions were asked in parliament as to why the DND should be trusted with nuclear submarines when it couldn’t even defend its own HQ. The Tories were deeply embarrassed and to avoid further humiliation, they canceled the planned announcement of the choice of submarines.

Several weeks later the Conservatives called a general election. During the election campaign, they promised two billion for universal free childcare. After winning re-election, they pulled off an astonishing political trick by claiming that they had not realized the state of the government’s finances. This might be reasonable for a new government coming in, but stunning for one returning to office. Due to this sudden hole in the nation’s finances, they announced they couldn’t afford the cost of the promised universal childcare. Having announced they couldn’t afford two billion for childcare, they were unable to announce new spending of eight billion on submarines, and the plan was quietly dropped. The timing of the Greenpeace action had been critical. Had the submarines been announced before the election as the government had planned, they could have continued with the programme as previously agreed spending. As it had not been announced, they could hardly announce such a vast new programme given the ‘new’ budgetary situation. Following a long and widely supported campaign by numerous players, the submarines were an unpopular idea. The DND action blocked a decision on the submarines before the election and turned out to be the final nail in the coffin. This was perhaps the most successful action I ever did. More than 30 years later, Canada still hasn’t created the risk and waste of a nuclear-powered navy. Actions play an important role in Greenpeace campaigns. This action though may well have been the deciding factor in stopping Canada become the world’s 6th nuclear navy, and saved the taxpayers 30 billion dollars.

END

Those Yates cams. I couldn’t find a crack they fit until almost 45 years later when one went and locked in Tucker Carlson’s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi simon

I am leaving multiple comments hoping one lands on its feet like you and me. I love. Just to fact check you. There was no Ottawa canvas. It came from Toronto and Spyder and me we came because you were the man. Spyder knew you, I didnt. But we drove back together and you made me late to drink with Patti, damn you. I wish I had those days back to be with you.

LikeLike

If you aren’t dead, and would honour me with an audience, I’ll fly over for a Simon hug and I’ll give you my Buckeroo tavern shirt

LikeLike

Gary! I was talking about you to Steve shallhorn just a week or so ago. There was a NFS 35th anniversary meetup in London. More importantly, I miss you too!

I have a new pad, in the grounds of a Tudor mansion/palace in the middle of London! Sadly, no overnight guests, though we have a guest room which is occasionally free. Sadly, too, I am on an alcohol restricted drug, and so not drinking at the moment. Neither of these minor inconveniences should stop us meeting up. I’m simonwaters [at] rocketmail.com and 07923 889 307, so let me know whern you want to come.

LikeLike

I thought you were dead

LikeLike

I have been wondering where you were too.

LikeLike

Whoops

Sent from my iPhone

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike

Hi old mate. I miss you.

I just cycled through Rioja and around haro took off the training wheels. Remember me swinging back and forth in the chief not about to clean your lead and you said, before your grate yourself, Prussik up.‘I made the cru the next move. I miss you

LikeLike

I miss driving the clean and you making me listen to opera. You translated and I understood. You are my mentor

LikeLike

Hi simon

I miss you.

Canada

LikeLike

Hi simon

I miss you

LikeLike

I love this story, Simon! great storytelling and so interesting to read about a pioneering action that really made a difference!

LikeLike

Hello 🙂 I bookmarked this site. Thanks heaps for this!… if anyone else has anything, it would be much appreciated. Great website Super Google Guide Google Guide Enjoy!

LikeLike

Thanks Magne. I’d be delighted to see your opening chapter on the war in the Pacific, when available

LikeLike

Another great piece of writing, Simon. very exciting action, well told. and clearly well executed!

LikeLike

Simon, exciting and illustrative piece of writing. Peaceful demonstration can change the world. Your personality shines through, including your reflections upon the great care you took in minimising the risks that needed to be taken. What a historical prize was won. More please…meaning all of the rest please.

Big respect.

Gary.

LikeLike

Great piece Simon, edge of my seat for success and peril!

LikeLiked by 1 person