A physical comedy

20 minutes

It was the annual Festival of the Glorious Ewe, the patron saint of Mordek, and the capital was thronged with visitors. Kopek, chief spy of the Pimpleknuckle Confederation, surreptitiously mingled with the crowd disguised as a peasant on a jaunt to town, though his monocle and well waxed handlebar moustaches jarred slightly with his shepherds smock and slouch hat. He kept his eye on the guests arriving by coach or litter, climbing the great stone steps of the great Gothik town hall, to the crowded ballroom on the second floor.

Eustace Claricorne, deputy assistant to the Master of the Back Stairs, had dressed carefully for the grand reception and proudly wore the Mordek tricornered hat on his tousled head, and his myriad medals and badges above his ceremonial green and purple sash. He looked out of his turret window, high in the east wing of the town hall, with views of the spires and turrets of the town and of the vast throng filling the square below. It was vital that he do well today not only for Mordek, but for himself. Unfortunately, the day before had not gone well, accompanying the Master on a surreptitious visit to the Hedgehog embassy to promote an alliance against the threats of an invasion by Pimpleknuckle. Carelessly tripping over the embassy carpet, he had knocked over the ambassador’s portly wife. Today Eustace had strict instructions, in a note from the governor, to be on his best behaviour. The guest of honour at the grand reception was to be the irritable ambassador from Mordek’s warlike neighbour Pimpleknuckle himself. Pimpleknuckle claimed the border village of Gok, population 3 persons and 14 sheep, and sought a pretext to invade. It was important that the ambassador was not provoked, as a slight to his august person could be used as excuse for aggression.

As Eustace descended the back stairs from his quarters a trumpet cavalcade sounded from the steps of the Great Hall signalling the arrival of the Pimpleknuckle emissary. Eustace stuck his head into the grand ballroom. The mayor and alder folk were dressed in elegant costumes of lambs wool, with ewes horn hats, to honour the Grand Ewe. Eustace looked down the imposing grand staircase which swept from the ballroom to the mezzanine and down again to the grand entrance hall. Resplendent in his finest court regalia, he hurried to join the Governor by the great front doors. At the top of the grand staircase, he noticed his left shoelace was undone, and stooped to tie it.

A fall from grace

As he bent over, a waiter carrying a tray of empty glasses backed out of the ballroom, colliding with Eustace and knocking him forcefully forward. Eustace landed on his head, and rolled over the top stair. His speed was such that he continued to the second stair, and here (now going faster) over the third. At the bottom of the 26 stairs, as chance would have it, he collided with a large statue which slowed him down considerably. However, this wasn’t enough to stop him bouncing over the top step of the main staircase down to the lobby, again bouncing slightly faster onto the next step. By the time he hit the hall below, his descent had been observed, and a footman ran to close the great door, but too late. Rolling down the hall at a terrific pace, Eustace bowled over Madam the Governor who flew into the air and landed forcefully on top of the newly arrived Pimpleknuckian ambassador. Out the door Eustace shot! Bouncing down the top step at quite a speed, and progressively faster down each of the 12 stone steps, the deputy assistant to the Master of the Back Stairs, medals clashing against his gold braid, rolled into the main square, now gaily decorated for the festivities. He continued to roll across the great square, through the thick crowd, miraculously only bowling over the occasional surprised personages as he passed. Exiting the square, he tumbled at great speed down the steep hill that led to the town gates.

Upstairs in the reception room, there was a wave of incredulity. A half dozen near the door saw the Plenipotentiary, in all his well polished regalia, roll over the edge of the first stairs, and then suddenly reappear, glinting under the great candelabra, as he shot over the top step of the mezzanine. They relayed this astonishing sight to those standing near, and then a cry was heard from the crowd by the windows “Eustace is rolling down the square!” What to do was the question on many lips. The chief of police and the fire chief arrived by the mayor’s side from different directions. The police chief indicated by a small movement of his head that the fire chief should speak first. “I believe it would be opportune to go and investigate,” she said to the mayor. “Perhaps you will join me,” she added to the police chief.

These two officers, resplendent in their ceremonial uniforms, one bright red, the other a deep blue, hurried down the staircase, picking up a couple of members of their respective forces as they went. Unfortunately, though on official business, one of the firemen had over indulged on the delicious sweet wine. He was a large man and he followed tipsily along, slightly behind the others, and when he tripped on the top step he fell against the two policemen a few steps below him. The policemen fell, like well trained skittles, knocking both the fire chief and the chief of police off their feet and into a tumble down the stairs.

The only one not to get knocked off her feet was the second fireman, who bravely grabbed at her colleague’s arm, getting a good grip as he went past. The first fireman being of large proportions, and she of slight build, this did not slow him down. Instead it jerked her into the air, feet straight out behind her, and she joined him in his revolutions. At the bottom of the first flight of stairs these officials bounced, each in their own particular way, as they rolled across the landing, bumping into several footmen who tried to arrest their fall. Instead they all, now including two footmen and a maid, continued at high speed over the top of the first stair of the main staircase. Downwards, a melee of colourful uniforms, they bounced from stair to stair. Onwards they rolled, like giant cheeses, or hogsheads of claret, across the entrance hall and, unfortunately for protocol, over the prostrate Pimpleknuckian ambassador and his retinue. They bounced on through the still-open door and down the great stairs into the main square.

This too of course was seen from above, and a multitude of the guests proclaimed their shock and horror, or went for a strong drink, or sat down stunned, or all three of the above. However, the rush of the more practical to help was a tonic to see. Two dozen guests, including many of the nations leading officials, dashed to the stairs to go down and assist the victims. In their rush out of the ballroom, the crowd swept the first of the aid party brusquely over the top step. As they stumbled, a few managed to regain their footing, but those behind them, shoved in their turn by the surge to help, toppled them again and they joined the others, cartwheeling down the stairs. On the landing they met little resistance, it having been swept almost clear by their predecessors. However, they did add a minor duchess, who had been unmolested by the passing of the emergency personnel. Onward they rolled, a great tumbling mass of dignitaries and lesser members of officialdom, all now united by the wonders of gravitational attraction.

By now the Eustace, the first to fall, had left the square and was rolling with some speed through the town, causing some collateral damage to the occasional latecomer. He first collided with Esmeralda the lady librarian, who most unfortunately had just lifted her front foot when struck, and pivoting on her back foot, she too began to roll with great speed, and given the loveliness of her bright red dress, great effect. The Tardy-Jones family, perennially late, were just entering the road from a side street and got the full effect of the rotating red dress alongside the man spinning in his gold filigree court dress. “Bravo” they cried, impressed with the elegant display. As it was an important festive occasion, extra guards had been deployed, and the town gate was open. Out they rolled, ornate gentleman and brightly dressed lady librarian, past an astonished gate guard who shouted to his friend on the parapet above. The tower guard heard a cry and looked down. “No,” shouted the gatekeeper, “look to the road”. The tower guard turned around to the road outside the gate, and saw the astonishing sight of a man rolling along at high speed accompanied by a lady in a brilliant red dress. “Stop in the name of the Governor”, he called, but to no apparent effect.

By this time, those embodiments of public order, the chiefs of police and fire, and their attendant minions, were rolling expeditiously across the main square. Given their number, and in several cases large mass, they wrought more havoc, or to put it more scientifically, had greater material effect, upon the body of revellers than the passing of the Deputy assistant to the Master of the Back Stairs. With an accuracy that would have greatly improved the towns chances in the recent national 10-pin bowling tournament, they cut a wide swathe across the square. Their inverted V of well aimed blows and clouts upon the assembled personages caused a profusion of response vectors as each individual reacted independently to the strike force imposed upon them. But, marvellously undeterred by any extraneous contact, the mass of officials rolled, and frankly bounced and hurtled, towards the steep hill leading to the town gates. Before the crowd had begun to recover, or even had had a chance to reflect upon their condition, a third wave of personages came streaming down the great steps of the town hall, and added their portion to the general confusion.

This last wave, was made all the more elegant by the presence of a, even if minor, duchess, her diamonds glittering charmingly in the afternoon sun. They too bounced and hurtled, through, over and across the by now largely supine crowd, thwacking one here, thumping another there, and generally clobbering the last of those still standing. Generally, those struck by the passing ‘rollers’ were flattened, but some instead joined the mass descent of the hill below the square. The specific reasons for one response or another is a field of great interest to science, and has been the topic of considerable conjecture. We will leave this inquiry to others and merely report the facts as they are known. Apart from the first two rollers, the second group began with six or seven officials, recruited two footmen and a maid upon the first landing, and lost one member in crossing the great hall. As they crossed the square, however, their numbers were replenished by a balloon seller, a toffee apple man, three brave, if foolish, policemen, and several visitors to the festivities, whose positions in society are as yet unknown (though one was reported to have sported a handlebar moustache and monocle). This large group swept a large swathe of persons off their feet who either collapsed or cascaded into others, so that by the time of the arrival of the third group, by then numbering seventeen officials and dignitaries, and a glittering duchess, their route though the square was largely clear of those still vertical. Of interest to physicists, but unfortunately beyond the scope of this reportage, was the fact that several persons who had been sent hurtling off towards the extremities of the square rebounded and in their turn discombobulated the trajectories of several members of the third, and by far the largest, group to hurtle across the square.

Unknown to Mordek, it was not Pimpleknuckle that was the great threat. The small but efficient army of neighbouring statelet of Grimchek had been dispatched to attack Mordek some weeks earlier. The Grimchek troops were under the leadership of the notorious General Handlebar, the hero of the Great Chicken War. However, due to a misunderstanding of mapcraft in the Grimchek Ministry of War, the map of Mordek had been printed upside down with north at the bottom. By diligently following the wrong directions the Grimchek forces had spent quite several weeks lost in the woods of lower Mordek and were unaware of the recently agreed truce. Now, after their myriad difficulties in the woods, they were finally approaching the town, climbing the long and steep road towards the town gates led by a marching band, featuring tubas, ukuleles and penny whistles, playing martial airs.

As the army of Grimchek climbed the road, they were met by three successive waves of ‘rollers’, now known to the world as the ‘Descent of the Mordek Patriots’. There has been some quibbling in the media, that the physics of gravity would make impossible manoeuvring around the corners on the long descent to the valley below the town. I can only state the facts. In spite of, or perhaps due to, the winding nature of the road that descended into the deep valley below the town, the numerous rollers swerved around the corners and kept to the road. This is of course apart from a few unfortunate exceptions- the navel attaché for example, became stuck in a thorn tree on the first bend.

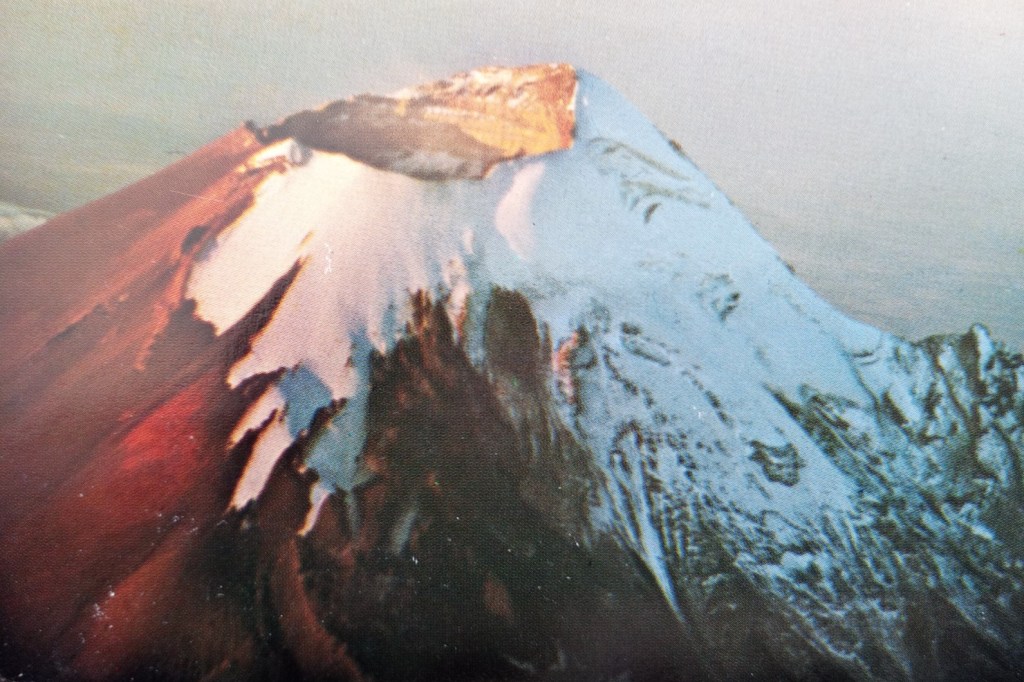

Eustace and Esmeralda swept majestically down the steep hill, defying the small minded notions of foreign physicists, taking the corners with ease and elegance as they swept ever faster past the magnificent views of the verdant valley below, backed by distant mountains catching the afternoon sun. Eventually they turned a corner and sped down upon the advance guard of the invading army. They arrived so unexpectedly, and with such speed that they were met with no resistance, and swept through the company, elegantly bowling many of them off the roadside cliff. Before they had time to recover from this first pair, the advanced guard was almost immediately struck by a larger body, in both senses. The oversized drunken fireman, wobbling as wildly as he rolled speedily, crashed through the remaining upright soldiers. He was quickly followed by his many companions of the fire service and police during this second assault, who having dispatched the advanced guard, swept on towards the main body of troops.

General Handlebar, riding his great black stallion Coltrane, rode at the head of the main body of his army. Eustace and Esmeralda passed, one each side of the mounted general, each taking out a line of troops. The general, astonished by this hideous new weapon of war, turned to bark an order, but was immediately driven off his horse by the portly fireman, now advancing at a most warlike rotation. The general’s horse, panicked at the sudden loss of his commander, now turned tail and joined the rout caused by the first wave of gyrators and added considerably to the confusion. Dropping their guns, abandoning their cannon, leaving their tambourines and ukuleles scattered across the road, the army fled, though not fast enough to avoid the arrival of the majority of the second wave. There was little left for the third wave to topple, and the diamonds of the duchess shone impressively in the late afternoon light as she hurtled over the now largely prostate figures.

[To be ended shortly]