South from Tamanrasset

15 minutes

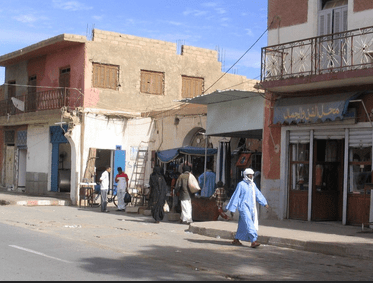

At the camp ground in Tamanrasset there was a group of five Italian junkies who had decided to hitch-hike across the Sahara to get off heroin. Tamanrasset is the southernmost town in Algeria, sitting almost in the middle of the great desert. In 1972, the town was small with just one or two cafe-bars, and a few shops on the single boulevard, a baker or two, a small municipal market, some government offices, a military base and an air strip.

The Algerian government had a policy that a few basic items would be sold at the same subsidised price everywhere in the country, so that a baguette, or a tin of sardines in Tamanrasset cost no more than it did in Algiers. As we were almost 2,000 km south of the Mediterranean, everything else that was brought in was very expensive. I had left England with about £150, and had been on the road for five or six weeks, so in order to stay solvent as far as the coast of west Africa, I was living on baguette and tinned sardines from the government shops, and the small onions, tomatoes and dried dates from the market. There was a tap with cool, clean water in the small camp-ground just off the boulevard, where a few other hitch-hikers and the occasional overland driver rested before moving onto the next, most difficult, section of the desert.

When I arrived in the camp-ground there was no one going south with a vehicle apart from a Frenchman, Jacques, who was waiting for a part to fix his car. Tamanrasset is on the edge of the Ahaggar, and visiting these wonderful eroded mountains rising to almost 10,000 feet, had been the reason I’d changed my travel plans and not gone down the coast route through Mauritania.

https://www.petitfute.co.uk/v41839-tamanrasset/guide-touristique/photos.html

Some good desert photos near Tamanrasset

I made a trip to the heart of the Ahaggar, where I camped for several days, then returned to Tamanrasset to find a ride south.

Tamanrasset didn’t feel like the desert. It wasn’t even an oasis, more a French military camp with a small dusty town attached. The Italian junkies were still looking for a ride, and Jacques, the French psychologist, who had been at the camp when I first arrived, was still waiting for his part. He was travelling alone in a Renault 4L, and had broken his back axle 100 km north of Tamanrasset. He’d spent 3 weeks stuck in a tiny mud-walled Tuareg village before getting towed into Tamanrasset, where he had been waiting another two weeks for a replacement axle to be flown in. Every day I wandered over to his campsite and practised my lousy French, gradually learning his story, and sharing mundane information about our families and work. I was quite happy to discuss the number of my sisters, and the distance between my house and Trafalgar square, and learn about his own sisters’ children, their ages and names, and how many miles his town was from Paris, as any communication improved my French. I did slightly wonder what was in it for him. I had hoped for a ride south with him, but he’d already committed to giving a ride to a local who knew the route.

After about ten days, with no sign of a ride south, things were getting pretty dull. There was a small turnover of travellers in town, as some people flew in from Algiers for a week, and some overlanders had reached their journey’s end and were planning on returning north. The Italians found a ride with a pair of Land Rovers and made a deal to take them all. They left one morning, and the camp ground was now almost empty. I was beginning to think I might have to pay for a place on the next truck south, but I still really wanted to hitch-hike across the Sahara. One night wandering in the administrative district, I found a small bar with tables under tamarisk trees, and ended up drinking with the head of immigration. Having bought me several drinks at the end of the night, he told me, very drunk, that he enjoyed my company, and wouldn’t give me the necessary exit permit to leave town, as he wanted to keep me around to talk to. I didn’t know how seriously to take this, but it didn’t look good.

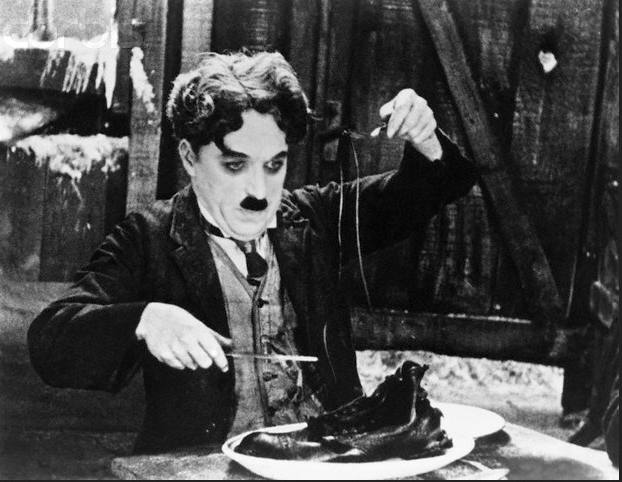

The next day, walking on the boulevard, Jacques screeched to a halt in his Renault 4L. “On y va” (Let’s go!), he said. His vehicle was fixed and his passenger had changed his mind. If I wanted a ride, I had to leave with him, Now! I plead for 20 minutes to make my arrangements, and ran to the government store and bought a dozen tins of sardines, six long baguettes, and half a dozen two litre bottles of water, then back to the camp to throw my kit and a kilo of dates I’d bought earlier into my backpack, while Jacques hovered impatiently.

It was about 1,000 kilometres to Agadez the first town in Niger. We were on the main route across the Sahara, but this next section was largely roadless, and there were at most several vehicles a week. Jacques drove out of town at almost 100km an hour, and nearly left the gravel road on the first turn. He had already lost six weeks waiting for a replacement axle. It looked like he might now easily roll the car. I pulled out my small English/French dictionary and tried to translate “more haste, less speed.”

Jacques drove on into the afternoon at a barely moderated speed, braking sharply for the occasional sharp dips, then accelerating again. After an hour we were flagged down by the Italian junkies and several others, standing by two Land Rovers. They had broken down in the desert and the two drivers had hitched a ride back into town on a passing truck to get spare parts. They had been left two days earlier, and were almost out of food and water! Jacques filled up all their bottles from a jerrycan, and I gave them a couple of my bottled waters, a couple of baguettes, some dates and tins of sardines. We didn’t stay long. Jacques took off at speed and we tore along the gravel track for another hour, until a great hole appeared ahead of us. Jacques jammed hard on the breaks, and the roof rack slid down over the bonnet. We careened to a halt, running over the roof rack. “Dégueulasse!” said Jacques. I was to hear this word a lot from Jacques, and learned its meaning in context of one cock-up after another.

We got out and found that several of the fuel and water containers were punctured and draining into the desert. “Dégueulasse!” again. Fortunately, Jacques had a spare roof rack (!) and so he set about assembling it. I have the vivid memory of bedding down in my sleeping bag in the completely flat gravelly desert, and watching the sun sink in the west as a full moon rose in the east. As I fell asleep, Jacques began the assembly, following IKEA like instructions. Attache un a deux. I woke as the sun rose and the full moon sank into the west and Jacques was finishing up the roof rack: attache trente quatre a trente cinq. I took it for granted that Jacques had spent the whole night building the new roof rack. We put it on together, reloaded the remaining fuel and water and tore off again.

Soon the rough track ended, and we were driving across a gravel plain following a couple of sets of tire tracks. The tracks were made by overloaded ten ton trucks, and were far too deep for us to drive in. But we drove easily alongside the truck tracks, sometimes making our own ruts and sometimes staying up on the hard surface. This is the desert pavement (known as reg) that covers much of the Sahara. Jacques continued to drive at a great speed, occasionally crashing into small hollows he hadn’t time to brake for. As we drove, suddenly the ground would be harder, and there were no tracks to follow. As we were driving so fast, we were instantly in a trackless wilderness. We would drive until we came out of the hardpan, then swing right and left looking for the truck tracks. Sometimes we found them quickly, sometimes they were not to be seen. As the desert was flat and featureless, and we were speeding across it and sweeping from side to side, when we got lost it was very hard to know which side of the tracks we were on. We might easily have strayed a mile or more off track.

Occasionally we got bogged down in soft sand, and had to dig out. As there were only several vehicles a week on this trans-boundary section of the route, and often they convoyed, it was possible to not see another vehicle for a week. Worse, if we got a couple of miles off the track, and then broke down, we wouldn’t necessarily be able to hail a passing vehicle as they’d be too far away. There were too many tales of lone vehicles getting into trouble, and in the previous winter an American couple with their two children had broken down and they had all died. The advice was strongly against travelling in a single vehicle.

Sometimes Jacques would have an idea which way to go, when we lost the tracks, sometimes he depended on me. All this done at a mad rush. We had troubling minutes as we swept back and forth across the desert looking for the route. When I had absolutely no idea which way to go, which happened several times, I would say, “A gauche,” keep left, on basic political principle. Fortunately with this technique we always found the tire tracks again. But, driving so fast over the rocky ground, we were getting a lot of punctures, and had to stop several times to change tires. Each time we stopped we also used up a lot of water refilling the radiator, which boiled dry in no time. Jacques had three spare tires, and soon we had used two. Then we had to use the third and so no longer had a spare. It is hard to keep track of distance in a largely featureless desert, but the mileometer said we should be at the border. The one piece of information I had was that when you see the border flag, don’t drive straight at it, as there is a sand trap right in front of the border post. After a harrowing hour, with no spare tire and a growing fear that we had missed the border, a kilometre or two in front of us was the flag. “A gauche!” I said, but we were already in the sand trap, and so Jacques applied his universal answer to all problems, and gunned the engine. We began to slither and we were quickly losing momentum. Jacques gunned the engine again, and we slithered on until we found solid ground and picked up speed. Phew. We pulled into the border post, a most lonely looking affair of a few adobe buildings, a barrier and a giant flagpole. This place was so isolated that, rarest of situations, the border police were very happy to see us and welcoming. Fortunately, the post had a tire repair service, but no spare petrol, so we would need to get more somehow.

After we had completed formalities, filled our water containers from the well, and waited an hour or two to get three punctures repaired, we set off into Niger. This was the most isolated 500 km of our journey, with the next several hundred kilometres again roadless, and Jacques planned on doing it in two days. We went through a section where there was nothing growing, and no features of interest, just a great expanse of flat gravel desert. I amused myself by looking for an entirely featureless place, but was unable to find it. The closest I got was a place where there was no tree or shrub or other feature on the vast plain, and an entirely flat horizon for 340 degrees. Then, far off, three low rises covered 20 degrees of the horizon. Here we got another puncture. When we had replaced the tire, it was dark and we spent another night out.

The next morning, the car wouldn’t start. I watched as Jacques took the lid off the carburettor and cleaned out several table spoons of sand that had gotten inside. When he put the carburettor back together and turned the key, the engine coughed. After a few tries it burst into life and we took off again, to a morning spent stopping to replace punctured tires and refilling the radiator between short bursts of speeding. Suddenly, a tiny village loomed out of a desert haze. There was a well with a small settlement around it called Tegguidda-n-Tessoum. We pulled up and stopped at a low mud wall near the well. Goats, and camels were herded up to water at the troughs, which were filled by buckets from the well. The map said the well was ‘salines/salty’, and Jacques didn’t want to bother to fill the water containers. We were using a lot of water refilling the radiator several times a day, and we were drinking a lot too. I managed to get across in my poor French, that if we don’t need the water it wont matter that it’s salty. And, if we do need it, we wont worry that it’s salty. After filling up the couple of empty jerrycans and returning to the car, we found that another tire had gone flat. We had again run out of spares.

Astonishingly, within an hour a large truck pulled up, and Jacques hitched a ride to Agadez. He took the four flat tires, and two empty containers for petrol. I stayed behind to look after the car and our stuff.

Three days at Tegguidda-n-Tessoum, salt mine and watering hole.

As Jacques drove off, I was surrounded by a great sense of silence. I walked around the small settlement, the only one for a hundred kilometres. The village was a dozen simple adobe houses in small compounds, with three foot high walls that, ignoring simple geometry, wandered far off a straight line as they rose and fell. There were some bleached bones and a sardine can or two stuck along the top of the walls.

At the well, herds were watered in the morning and evening by pulling a goatskin bucket up from the deep well and pouring it into a series of troughs. Sometimes a camel was used to pull up the bucket, sometimes a donkey. Herds of goats, donkeys and camels were watered in a cacophony of bleating, and lowing. After the herds were watered, they were led away and a great silence fell. Beside the village was a salt mine where several men washed the sand to produce discs of sandy salt. Over the next days, several herds arrived and watered. One morning, I woke to an eerie sound and getting up saw a large herd of donkeys being watered in the dawn mist. A camel caravan arrived bringing food (millet, beans, maize, cheese and dried vegetables) and other goods to trade for the salt, which was only used for animals as it was a yellow colour and 50% sand.

This is a detailed description of the Tuareg salt trade, with excellent pictures

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/africa/tuareg_salt_caravans/index.php

As the days passed, I lived through a combination of awe inspiring sights and sounds and lethargic boredom- the essence of low-bagging travel. There was a small shop in the settlement, in the front room of a house. There were just a dozen or so things on sale: biscuits, combs, batteries…

After three days, a VW bus arrived but neither of the Germans spoke English.

“Friend, Agadez” the driver said, and gave me the four repaired tires and two jerry cans full of petrol. OK, I thought, he’s left it to me to drive the car to Agadez. It would be the first time I’d hitch-hiked with my own car!

I put one spare on the car, and loaded up the other three spares, and the jerry cans of water and petrol, and went to say good bye to my hosts in the village. When I came back to the car, the Germans were nowhere to be seen, as I drove off into the afternoon. After about 25 kilometres, I saw a woman walking alone across the desert towards me. I stopped and asked her in my poor French where she was going, but she didn’t understand, and replied in another language. She had a small bag on her shoulder and a metal teapot of water balanced on her head. I thought, she couldn’t be going far, there must be a settlement nearby, so I turned around, and offered her a ride, expecting to soon see a nomad camp. We drove for a while, and I tried to understand where she was going. In 45 minutes, I had driven all the way back to Tegguidda-n-Tessoum.

I stopped 500 m from the village and dropped her off- as I didn’t want to get caught up in further goodbyes. There was a tremendous whistling and hollering, but I ignored the noise, turned around and drove back into the desert. After an hour or so, the engine spluttered to a halt. It was now late afternoon, and I got out and propped open the hood. The radiator was boiling over, so I carefully took off the cap, dodging the fountain of boiling water, and after a number of blowbacks, got most of a jerry can into the radiator. The car still wouldn’t start.

The only thing I knew about was watching Jacques clean the carburettor. I got out the tool box and found a wrench to take off the nut on the carburettor and remove the cap. It was full of sand. I fiddled with a teaspoon and managed to remove most of it. Putting the carb back together I dropped a nut into the engine. It pinged, and fell through into the sand below. It was now almost dark. I looked under the car, but decided that if I looked for the nut in the dark, I’d bury it for ever in the sand. I rolled out my sleeping bag and got in. As I fell asleep, I had a short panic. If there was a sandstorm, or even a strong wind in the night, I might have real trouble finding the small nut when I got up.

I hoped I wasn’t saying “Dégueulasse!” myself in the morning

Next Onwards to Agadez, if the car starts.