Greenpeace and the US/Russia Summit in Vancouver 1993

Video links at end of piece.

There had been real hope that when Bill Clinton met Boris Yeltsin in Vancouver on April 3rd and 4th 1993, their summit would lead to an agreement to end nuclear testing. But as the planning for the meeting progressed, Greenpeace Canada nuclear campaigner Steve Shallhorn learned that a test ban had slipped from being potentially the top of the agenda. It was now not even on the list of topics the two presidents were scheduled to discuss.

In 1993, Greenpeace Canada had no action team in the west, and I was hired on contract when an action coordinator was needed. So Steve called me into the Greenpeace office and told me he wanted to do an action to get ending nuclear testing back on the table when the presidents met. We went together to Canada Place, a vast tent-like structure on Vancouver’s waterfront, where the formal part of the meeting would take place. I had previously scouted this building (out of professional curiosity), and had documented how to climb the great cables that held the roof on. But I knew that there would be no way we would get near the building, never mind onto it, when Boris and Bill were in town. We later learned that security around the meeting sites was to be provided by 2,000 Royal Canadian Mounted Police, as well as the US and Canadian secret services. They guarded all access roads; all manhole covers were sealed and all mailboxes and news stands were removed from the area. Whilst it had never crossed my mind to hide in a sewer, or hang a banner on a mailbox, it was obvious that security would be tight.

It was still two weeks before the meeting, so there was no problem walking around the esplanade which surrounds Canada Place. Steve and I looked for a building overlooking it, from which we could hang a banner that would be visible, at least notionally, to the two presidents. There were a number of office towers, but access to their roofs would be impossible, as they might be seen as possible sniper hideouts. Steve pointed out a tall tower half a mile away in the distance with a giant W on the top. It seemed to be the only option, so I went to see it up close. The tower was on top of the Woodwards department store in the down town east-side. The main building was five or six stories high, with a multi-story rectangular tower that rose another twenty metres above the roof top. On top of this tower was a 25 metre replica of the Eiffel tower, with Woodward’s landmark “W” installed on top of it. The W lit up at night and revolved to advertise what had once been the top department store in Vancouver. The front of the store was on a busy shopping street, but behind the store was a much quieter street, with a multi-story car park from which a three story bridge crossed to Woodwards. From the roof of the car park I could see that we could walk across the roof of the bridge and get onto the store’s fire escape. But from the top of the fire escape to the roof of the store was a twelve foot blank wall. Once on the store’s roof, we still had the problem of accessing the roof tower, which would probably be locked.

I phoned up the store and, posing as a photographer working for a postcard company. The next day I met a charming young woman in the management office, who took me to the roof of the store, where I checked out the possibilities for tourist postcards. I then asked to see the roof of the tower. She took out a bunch of keys and unlocked the tower door. Fortunately, it had a push bar to exit from the inside. Climbing a series of stairways past vast tanks which held central heating oil, we emerged onto the roof of the tank tower, which was perhaps 30 feet square. From here rose the mini Eiffel tower that held the W. The staffer wouldn’t let me climb the tower – something I needed to do to measure the W for a banner, and to see if there was a switch up there to get the W revolving. Consistent with my cover story, I said I’d book a crew and return in a week to do a shoot. I had to return on the day before the action as I planned to hide someone in the tower to let the climbers in and I could hardly leave them there for days. I’d have to hope that the weather was fine the day before the action, as it wouldn’t work asking to go on the roof to take photographs in a heavy rain.

The tanks tower, the mini-Eiffel tower, and the revolving W

After seven years doing actions for Greenpeace, I had been arrested so often I now usually managed other climbers, and stayed out of arrest situations. So I needed two climbers, and one of them would need to be very experienced. Fortuitously, Brian Beard, who had joined me on my first action on the Cambie Street bridge [see previous blog] had just got back in touch. The Greenpeace offices were bugged, and as this action was of concern to Canada’s secret service, I called Brian in Edmonton from my home phone, and asked him if he’d like to come to Vancouver for a few days to go climbing with me the following week. He got the message. The other climber was Dean from the Toronto office, who had had Greenpeace climbing training and done a few actions already. He was calm under pressure and highly competent but this would be a challenge. My plan was complicated, and the banners would be very high and would be susceptible to any wind. The banners were made by a friendly sailmaker, and if you think of how the wind drives a sailing boat, you realise that a banner filled with wind will pull against its attachment with a great deal of force and, as the tower was an open girder structure, it would catch the wind whichever direction it came from. Dean would be safe as long as he was accompanied by an experienced climber. Fortunately I had complete faith in Brian. They arrived just a couple of days before the action and both worked amazingly well together to finalise their equipment, plan the banner deployment, train together and pack the rucksacks.

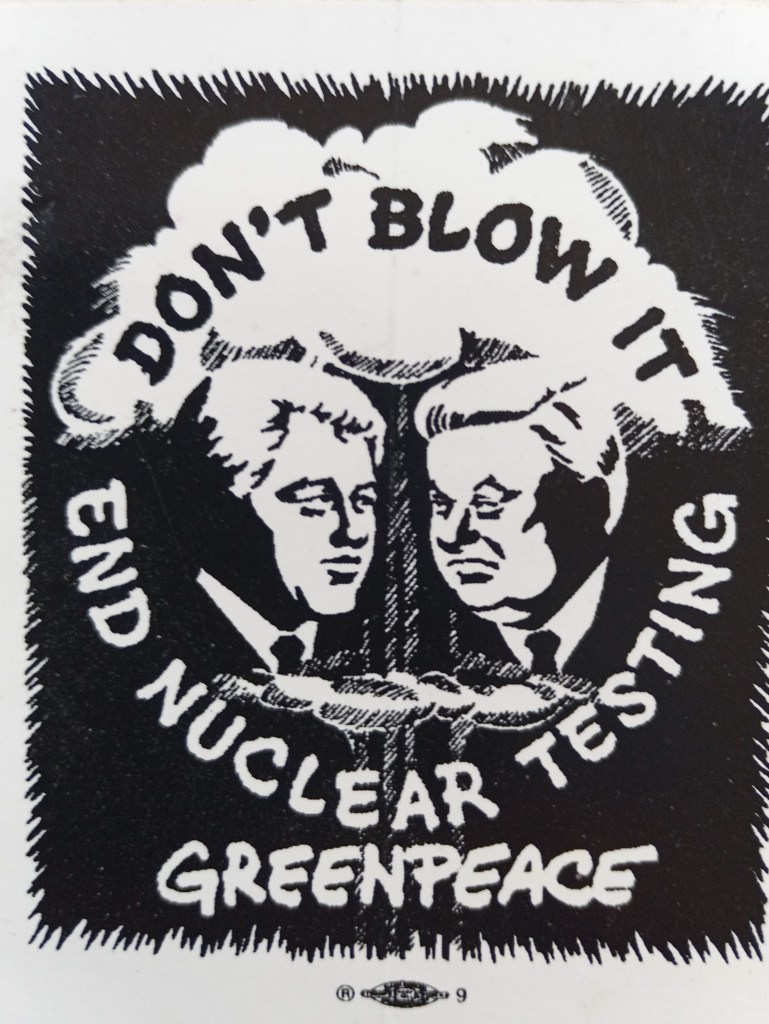

This had to be a big and dramatic action as we were targetting the US and international news media. I had ordered two large banners so that we could get out our message in both English and Russian.

Both these banners would optimally be visible from the summit meeting at Canada place.

I also wanted to put Bill and Boris on either side of the W, on the top of the tower, as icing on the cake. Optimally, we could get the W to spin and so address our message directly to each of them. Bill Stop Nuclear Testing; Boris Stop Nuclear Testing (for the Americans) and the same in Russian. I needed to be sure of the W’s size before I ordered the name banners, so I went to the city hall planning department and found the plans. There were numerous sketches of the tower and the mini Eiffel tower, but curiously none of them showed the size of the W. I guestimated it was big enough to fit a 12 foot by 10 foot banner, and ordered two. Steve had asked for the banners in English and Russian. I told him of my idea for Bill and Boris on the W, and he let me get on with it and spend what I needed.

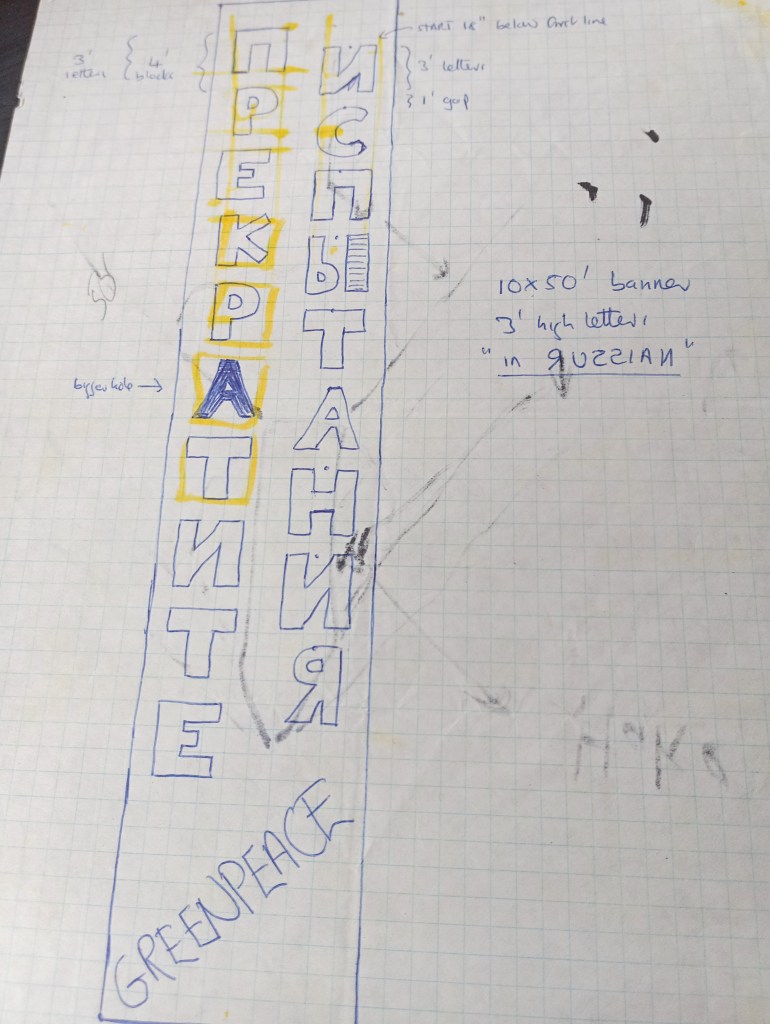

Sketch for lettering Russian banner

Dima Litvinov the Russian campaigner, in town for the summit, gave me the translation of “Stop Nuclear Testing”, which is just “Stop Testing” in Russian. I spent some time fiddling to get it to look good on a vertical banner. I usually did the lettering with the Greenpeace canvassers who finished work at 9 or 10pm. I bought a case of beer and ordered in plenty of good pizzas, and we worked into the early morning, moving desks and taking over the office. As we had four banners, this took several nights.

We had always used an expensive ink to letter the banners. This meant laying out as much banner as we had floor space for between the desks, and waiting for it to dry before moving on to the next section. There was a risk of spillage, so the work had to be done very carefully, and an inked banner slogan could not be changed, as the ink was permanent. Banners were rarely reused, as even if you wanted the same slogan the banner size might not be appropriate for the next site.

So, I had developed a different system, pencilling in the outlines of the words and using black duct tape to fill in the letters. This was quicker, didn’t require waiting for the banner to dry, and meant the slogan could be stripped off or modified so that banners became reusable. This saved thousands of dollars (I was using top quality sail cloth and paying about $2,000 for a large banner), and allowed us to reuse banners with new slogans and do extra actions, even when there was little or no budget.

Now I needed to know if we could get access to the Eiffel tower platform and whether there was a switch for the W. And, I absolutely had to get someone hidden to let the climbers into the locked tank tower.

The weather forecast for the summit meeting was strong winds and heavy rain, so we brought the action forward a day. I was able to book a shoot on the roof of Woodwards two days before the summit opened, and fortunately, it was a clear day. I now needed a camera crew, which I again recruited from the Greenpeace door to door canvas team. Canvassers dress casually, and we needed quite a bit of borrowing to replace patched trousers with more upmarket clothing to make the film crew look passably professional. We also needed a professional camera kit and someone able to use it convincingly. And lastly we needed a volunteer to hide and spend the night in the tanks tower, to open the door from the inside, prop it open and then to drop a rope for the other climbers coming up the fire escape with the kit. Dean volunteered for this dull, cold job, even though he was also going to be hanging the banner.

On April 1st, I returned to the Woodwards roof, with the camera crew. There were four of us, me as director, one of the canvassers playing a photographer carrying an impressive array of borrowed cameras, with Dean and another assistant to help him. The photographer moved around setting up carefully composed photographs. I was hoping the Woodwards employee would leave us on the roof alone, but it was not to be. So, while one of the photographer’s assistants kept them busy, I set off to climb the tower. I wasn’t noticed until I was almost at the top, and pretended not to hear a call to come down, while my assistant assured the staffer I was used to working at heights. I found I could easily get onto the tower platform, and got a better idea of the W’s size from just underneath it, but couldn’t measure it without some dangerous gymnastics. It seemed the 10 x 12 foot banners would work. I also found a red electrical box that appeared to be the switch to start the W, then descended. As the photographer and his assistant finished up their work, I told Dean to quietly leave. We gave him five minutes to find a hiding place behind one of the oil tanks, then said we had finished. The staffer asked where our fourth person was, and I said they had had to leave as they were needed back in the office. We were politely escorted down the tower stairs, past the great oil tanks, and a hiding Dean, down through the building and out. This had been the tricky part. We now had someone on the inside to let us back in.

The news that night was full of the heavy security system in place for the summit. That evening I parked a rental van on the top floor of the parking lot behind the Woodwards building. From the drivers seat, I had a full view of the bridge across to Woodwards, the fire escape, the oil tank tower and the mini Eiffel tower with the W on top. I returned around 2am with Brian and a helper, who took all the gear from the van, hopped the railing, walked across the roof of the bridge and clambered onto Woodward’s fire escape. When they got to the top of the fire escape, to my relief, Dean lowered a rope and they prussiked up to the roof. Watching from my van, I had a nervous time as Dean kept his head over the parapet whilst they climbed. The climbers were hidden in shadow and not easily visible by the occasional pedestrians on the street below, but if they saw Dean on the roof, they might easily raise the alarm. I could not call to ask him to pull his head back from view as a shout might have caused people to look up and see him, so I waited tensely, and hoped to hell no one would look up. When they were both over the top, and out of sight, I relaxed. Then came many cold hours waiting to hear whether they had gotten up the mast and were ready to go.

The overnight wait is always nerve racking. That night the wind was strong and had a real bite and I was cold even sitting in the van. I hoped the climbers were fine and that I hadn’t over complicated their task in my desire to make the banner as spectacular as possible. I knew that Brian was both a safe and very experienced climber. But I was still worried given that he was setting up anchors in the dark, in a place he had not previously seen in daylight, and on a cold and increasingly windy night. If they’d been spotted climbing from the fire escape, or as they climbed the metal tower, they could potentially still be stopped. They were not necessarily able to get out of reach of interference as they set up the anchors on the platform at the top of the Eiffel tower. Their only defence would be that the third person on the roof would lock themselves onto the Eiffel tower’s metal ladder, making it unsafe for security or the police to pass them to get at the climbers.

In the morning I was in radio contact with Brian, and though they were finding the going slow, they were on track to unfurl the banners. We had a dramatic plan. The climbers would pull down the first vertical banner: “Stop Nuclear Testing-Greenpeace”, and then another vertical banner saying “Stop Testing” in Russian. Then the icing on the cake, they would set the W revolving and it would have Bill on one side and Boris on the other, so that as it spun it would say “Bill Stop Nuclear Testing- Greenpeace”/ and “Boris Stop Nuclear Testing -Greenpeace”; and “Boris Stop Testing” [in Russian] and “Bill Stop Testing” [in Russian].

In the morning, the banners unfurled like a dream.

It took a little while, but soon the W began to spin, and I was delighted. All this was filmed by half a dozen TV crews, and we made a big splash on the Canadian and US news as well as various international stations too.

After a couple of hours, with the high winds whipping the banners against the sharp edges of the tower, the bigger English banner began to tear. It didn’t take long to shed badly, and had to be dropped. The wind was cold and quite violent, so in the afternoon, the climbers came down. The store didn’t press charges, so the climbers walked free after a really brilliant job. The bigger the international event, the harder it is to get your voice heard. This meeting was a really top level summit, and yet we managed to get massive coverage on the day and evening before the Presidents arrived. Once you are in the news you are part of the story, and the further protests – following Yeltsin’s boat touring the harbour, were given good coverage too. Also the imagery of the presidents meeting was dull in comparison with Greenpeace’s actions. Most of the other protests were a crowd with banners, or another talking head. Not only did Greenpeace get coverage of our series of actions, and an opportunity to raise the issue, but when the presidents arrived the next day, the first question at the joint press conference was from the New York Times. Their reporter asked Clinton, “What are you doing about Nuclear Testing?”

This action wouldn’t have been possible without the enormous skill and dedication of both Brian Beard, the lead climber, and Dean Mercer, who successfully hid himself to spend a cold night in the tank tower, and then joined in the banner hanging. It’s lucky we did our action the day before the meeting started. When president Yeltsin arrived, he stepped off his Aeroflot jetliner into pouring rain.

Here is some positive media from the Canada’s CBC

Kiro TV (US)

Greenpeace protests at Bill and Boris Vancouver summit 1993. An action gives a Greenpeace spokesperson prime time to get out the Greenpeace message. But also notice how this US station includes the marginal Communist Party of Canada to muddy any positive message