Knots in Manali, and War with Pakistan

15 Minutes

[Following our ascent of a 17,000 foot ridge overlooking Tibet, we return for exams at the Himalayan Institute of Mountaineering, Manali.]

We packed up our tents at high camp, leaving three foot high pedestals of snow where our tents had stood, showing us how much the snow had melted in just a week or so. We descended to the tree-line camp. It was now late May, and spring was coming fast at 9,500 ft and the Beas river now showed as a large stream emerging from a tunnel of snow. After ten or twelve days camping on snow, it was time for a wash. I set up my airbed on the snow in front of my tent and had a flannel bath with a pot of hot water skived from the kitchen tent. I then ran barefoot across the snow, and jumped into the Beas, submerging for a second to rinse off the soap, ran back to the tent, and hurriedly redressed.

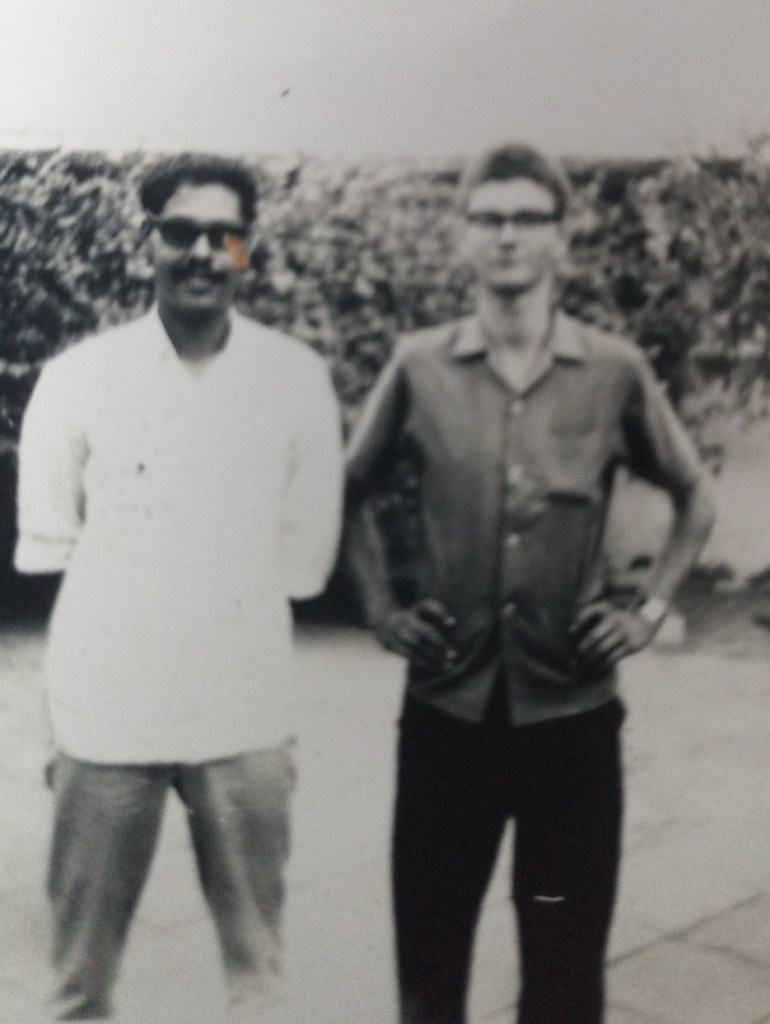

Back at Manali, we prepared for an interview with the director. We had been taught numerous knots on the course, and Dan Kumar had recently shown us a new knot, which was not in the curriculum. I spent the day before the interview practising the knots and swotting up on the vocabulary. When I went in to meet the director, Dan Kumar and Purshotum were there too. “I have had good reports”, the director said, then after a few questions on techniques and equipment, he asked me to demonstrate some knots. One of them was Dan Kumar’s new knot! I was thankful, I’d learned it too. I told the director, that I was hoping to receive an A, as I wanted to attend an advanced course. “We will have to see what we can do”, he told me. The next day we heard that fourteen of us got an A grade, the highest number on any course ever. With so many succeeding, I’d have to do some lobbying to be invited back.

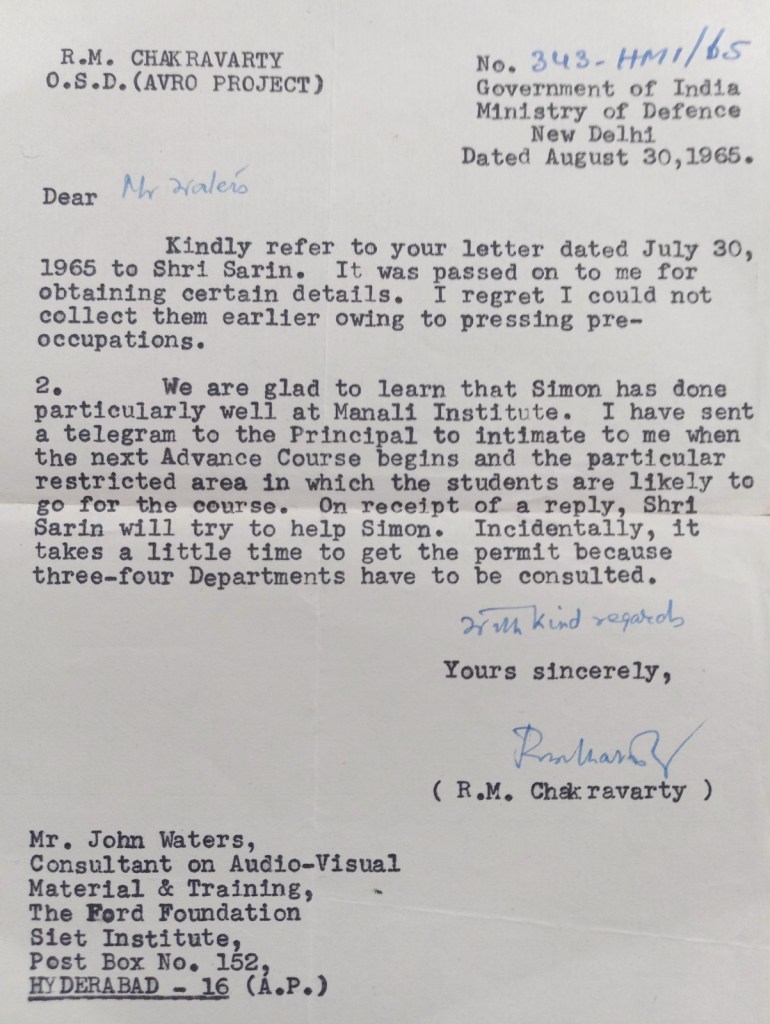

Back in Hyderabad, Jake received a letter from Mr Govind at the Ministry of Defence Production. “I hear that Simon has done well at the institute”. Unfortunately, the 7th advanced course in August was in a restricted area, over the Rohtang pass, and it was not possible to get me permission. However, I was welcome to go to the 8th advanced course beginning in September. This made me the first non-Indian ever invited to an advance course at the Himalayan Institute of Mountaineering.

With three months until the advanced course, I returned to my decadent neo-colonial lifestyle. I woke late, and went three times a week to sail at the sailing club on the artificial lake which separated Hyderabad from Secunderabad. The sailing was brilliant, in well maintained two person 1920s clinker built Eagles, faster plywood Enterprises, or in four person Moths, useful for taking out a larger party to picnic on the island. It was consistently sunny, but not too hot at 2,000 ft., with usually enough wind for good sailing.

Hyderabad is a fascinating place. It had been a Muslim state under a Nizam, with a Muslim ruling class and a Hindu majority population. The Nizam was reputed to have been the richest man in the world, and owned the diamond mine at Golconda. Some of the world’s great diamonds came from here including the Koh-i-noor diamond, part of the British crown jewels. Outdoing the Arabian sheiks who weighed themselves annually in gold, the Nizam weighed himself each year with diamonds! He had over 100 wives, and many hundreds of children.

Curiously, there was also a Maharaja with a palace in town (I dated his daughter twice, until a jealous rival told her parents about our secret meetings). Due to the Muslim tradition of separating their women folk in purdah, the Hindu’s were also hiding away their daughters. This made any hopes of getting a local girl-friend even less likely. The only girls who were allowed out apart from my two younger sisters were two white-blonde Mormon girls from Utah, who were much sought after by wealthy local young men.

In 1965, things were hotting up between India and Pakistan. When British India was divided, India claimed Hyderabad, in spite of the Nizam opting for Pakistan, on the grounds that the population was majority Hindu. However, they also claimed Kashmir, with its Muslim majority, on the grounds that the Rajah opted for India. This was perhaps due to Kashmir being Nehru’s birthplace. This had led to ongoing conflict between the two new neighbours, and Pakistan had invaded Kashmir that spring.

Apart from sailing, there was not much for me to do. My close friends Kamal, a Muslim and Vijay, a Hindu, were students in their early twenties, but still living at home and on a student budget. I had started working at 15, and saved enough to hitch-hike to India when I was 16. For some reason, though I had occasional use of the car, use of an account to eat and drink at the sailing club, and a very well stocked cellar at home, I never thought to ask for cash, so I was now penniless and stuck at home most of the time. This led to generally idle days and booze filled evenings. I drank my way through fifty cases of 24 Tuborg stubbies in just a few months, with the help of a few friends, and then moved onto VSOP cognac. Jake socialised exclusively with his Indian colleagues, who were interesting, intellectual, and nationalist. Here I first heard discussions on appropriate technology from Jake’s predecessor George McRobie, who returned for a long visit. He later took over the Institute of Appropriate Technology from Schumacher of “Small is Beautiful” fame. There were discussions about development: India didn’t need rockets, nuclear power and private cars (Nehru’s prescription) but a wider availability of bicycles, better ploughs and water pumps to promote development from the bottom up. However, this wasn’t sufficient to keep me fully occupied, and I longed to get back to the mountains.

As the day of departure for Manali drew near, the situation between India and Pakistan grew worse. There was talk of increased travel restrictions, and no-go areas. War hysteria had reached new heights, with groups of vigilantes scouring the streets for spies and saboteurs. This led to the lynching of an innocent young man in Delhi who was singing a just released movie song, which the crowd believed to be in Urdu (the language of Muslims and Pakistan). When I got to Delhi, I heard that all foreigners, including missionaries and nuns who had been there for decades, were being evicted as undesirable foreigners from the whole of Punjab. I hoped that, as Manali was high in the mountains, I might be able to avoid the restrictions: I just had to get there. However, when I got to Delhi station I discovered that all the trains north had been commandeered by the military. I was determined to get to Manali.

After chatting to some friendly troops on the platform, I boarded a troop train with a carriage full of junior officers on their way to the front. As the journey progressed, my companions chased off any inquisitive officials. Once off the train, I still had to pass through a number of checkpoints on the road north, with excitable policemen and soldiers looking for saboteurs and aliens. However, my letter confirming a place at the Himalayan Institute of Mountaineering, and some bravado, got me through each time. When I finally, I got to the institute, the director was stunned by my arrival. “How did you get here?” he asked, “This has been declared a restricted zone. I am very sorry, but I absolutely can’t let you stay here without a permit.” I was obliged to return to Delhi. There, I spent three days going from office to office at various ministries, until I got a permit to go back to Manali and the area where the course would be held. I phoned up the institute in triumph to hear, “I am afraid that the other students have not shown up and the course is cancelled.” I was told that I could return for another course, once the war was over.

I returned dejectedly to Hyderabad. Once there I followed the course of the war, now a series of major tank battles in Punjab, both on Indian and Pakistani radio. There were contradictory reports of daily advances of 10km for more than a week by Indian troops, though they didn’t get to Lahore which I knew to be less than 30km from the frontier. It was fascinating to watch how propaganda works. Most of my friends were certain that the news from their chosen media was correct (Muslims listened to Radio Pakistan, Hindus to All India Radio). Worse than that, apart from our delightfully cynical friend Saluddin, they were also all convinced that their chosen side was in the right, and winning. As the war progressed it seemed less and less likely that I could get on a course before the winter. I had been staying on in India since the end of May, just to attend the advanced course. In October, with no prospect of climbing until at least the spring, I returned to the UK. Far from becoming the best qualified British climber, with a trainers certificate from the Himalayan Institute of Mountaineering, Darjeeling (my goal), I didn’t climb in the mountains again until I discovered the volcanoes of Mexico ten years later. [See earlier blog: of Pulque and Popo]

Here are links to the two Himalayan Institutes of mountaineering- they still have bargain courses!

HIM in Darjeeling https://hmidarjeeling.com/

The HMI in Manali is also still going strong, under another name and management

https://www.tourmyindia.com/states/himachal/mountaineering-institute-manali.html

Interesting snapshot Simon. you do not say how many friends you had around help you wit the beer though? The fact that you did get a permit to go back for the course is amazing! would not happen today. please do write more!

LikeLike

A few, but madly, I drank most of it myself.

LikeLike

Thank you for you for your continued support. And i hope you are well

LikeLike